-

Teapot with cloud collar motif on cover and openwork knob

-

Chen Yongqing

-

Mark of (Chen) Yongqing (Chen Yongqing was active in early 17th century)

-

Height: 28.6 cm, Width: 22 cm

-

C81.418

A well-known potter of the 17th century, Chen Yongqing was active during the Tianqi and Chongzhen periods (1621–1644) of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

The dark brown stoneware of this massive teapot is embedded with fine grains to give a subtle "pear skin" texture. The dome-shaped cover has a globular finial, reticulated by piercing with a "cash" pattern and at the foot of which is a frieze of cloud collar pendants that enliven the solid form. The large curved spout and the ear-shaped loop handle placed opposite each other are in perfect balance, while the upper half of the body is surrounded by a raised band to give the bulky shape a more elegant form. A poem bearing an auspicious meaning of great achievement and success is carved on the body in simplified cursive script and followed by the signature of the potter, Chen Yongqing.

-

Teapot of chamfered low cylindrical shape

-

Chen Hongshou (1768–1822), Yang Pengnian (1796–1820)

-

Inscribed in yihai year of Jiaqing period (1815)

-

Inscription by Pinjia (Guo Lin): "Teapot number 1,379", Seals of (Yang) Pengnian; Amantuo Shi (Chen Hongshou)

-

Height : 7 cm Width : 11.8 cm

-

C81.496

The most representative patron of zisha teapot in the Qing dynasty was renowned seal carver, calligrapher and painter Chen Hongshou, alias Mansheng. He is said to have designed eighteen teapot styles when he served as Magistrate of Liyang and commissioned leading potter of the time, Yang Pengnian, to make teapots. The teapot with the seal mark "Pengnian" under the handle, "Amantuo Shi" on the base, and decorated with the poetry and signature of Chen Mansheng on the body, is known as "Mansheng teapot'.

This teapot bears a seal inscription on the shoulder that reads: "Teapot made by Shutao for

lifelong use". "Made at Sanglianli Studio in the 9th month of the yihai year, Jiaqing period. Teapot number 1,379". The bottom is carved with the names of Chen's fifteen friends and house guests in regular script, including "Jiang Tingxiang, Qian Shumei, Niu Feishi, Zhang Laojiang, Lu Xiaofu, Zhu Litang, Zhang Shengya, Shi Xinluo, Gao Shuangquan, Shi Lantang, Gao Wuzhuang, Miao Langfu, Sun Zhongpi, Shen Chunluo and Lu Xingqing" who assisted in the critical examination of the pot when having a literati gathering. Mansheng teapots not only owe their artistic features to craftsmanship, calligraphy and literature, but also to the overall design of the work.

-

Water dropper in form of hollow trunk with perching toad and mole-cricket

This masterpiece, a water dropper modelled as a hollow trunk and embellished with small creatures, was created by Jiang Rong. Produced as stationery for the scholar's studio, it features a mole cricket perched leisurely on the side of the spout, unaware of the approaching danger in the form of a toad on the other side of the hollow trunk. The potter has vividly captured the scene of nature's predatory behaviour thanks to her technical virtuosity and meticulous observation. The base of the water dropper bears the potter's seal marks "Jiang" and "Rong" in seal script.

Jiang Rong was born in a family of potters in the village of Qianluo of Yixing in Jiangsu province in 1919. From her childhood onwards, Jiang learned the art of Yixing pottery from her father, Jiang Honggao, and later from her uncle, Jiang Yanting. Honoured as a National Craft Master in 1993, she excels in modelling objects such as flowers and fruits in highly naturalistic colours and forms. By merging aesthetic beauty with naturalism, she has established her own unique style that has made her an outstanding Yixing pottery master.

-

Teapot of melon shape with swirling pattern in relief

Chen Mingyuan was the most eminent Yixing potter after Shi Dabin. His creations display great skill and ingenuity. He specialised in naturalistic teapots. This teapot is an example of his unique execution of segmented form. It is written in Famous Pottery of Yangxian that Chen's works was "sought after by scholars and intellectuals". Dating of this teapot remains an issue for further authentication.

This melon-shaped teapot is made of extremely dense and compact Yixing clay fortified with grains of sand to produce a "pear skin" texture. The lid has a knob simulating a stalk, while the handle and the spout are meticulously modelled in form of a stem. On the body near the underside of the spout is the potter's signature, "Mingyuan", inscribed in regular script.

-

Export teapot of globular shape with gold mount

Yixing teapots were first introduced into Thailand as early as the Ming dynasty (1368– 1644), while increasing quantities were exported there during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). These teapots were characterized by globular, cylindrical or pear-shaped bodies and a design incorporating metal overhead handles and glossy polished surfaces, while the spout, lid and knob were frequently embellished with metal rims. Many of these exports were small teapots commissioned by overseas Chinese so that they could brew gongfu tea, but traditional Yixing teapots in naturalistic shapes, for example in the form of truncated bamboo trees or trees with twisted overhead handles, were also popular in the Thai market.

This teapot is made of refined zisha or cinnabar clay. Its globular body is supported by three round legs. The highest points of the small spout and the handle rest in the same horizontal plane as the mouth of the teapot to form one of the typical elements of a gongfu teapot. The knob, rims of the lid and the mouth, the tip of the spout and legs are mounted in gold both for decoration and protection. The seal marks "125" and " Thailand " both in Thai characters are located on the flange and the base of the teapot respectively. This item is an outstanding example taken from a group of teapots commissioned by King Rama V of Thailand in 1907.

-

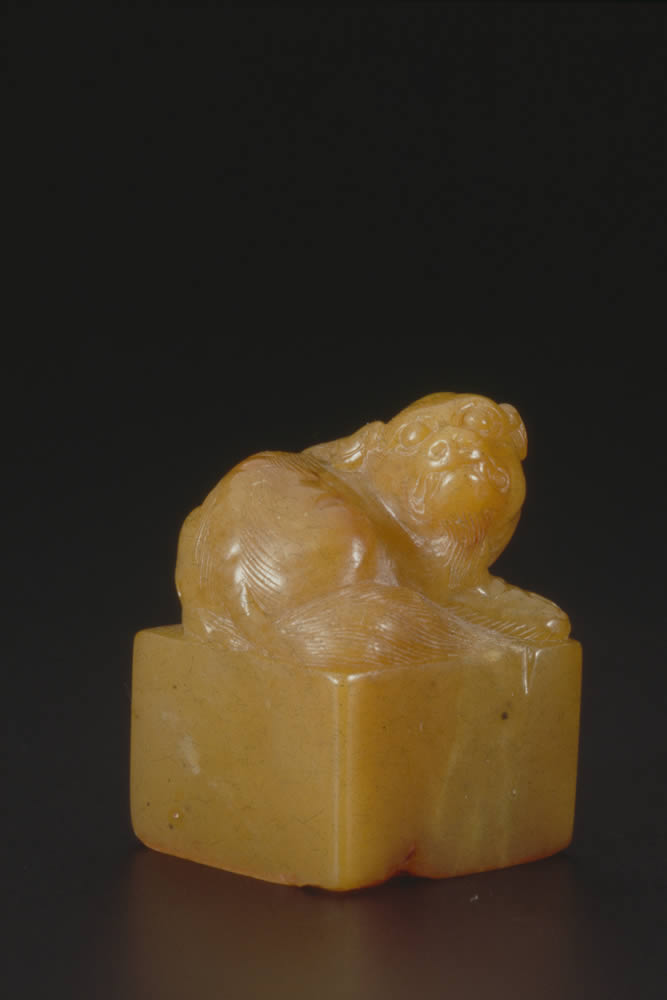

Square seal with four incised characters

This square seal is made of Tianhuang stone, a very rare type of monazite quarried under the silt of water-logged paddy fields in Shoushan village, near Fuzhou in Fujian province. It has a warm, rich honey colour that shows off its remarkable qualities. Because of its rarity, Tianhuang stone is regarded much more valuable than gold.

This seal was carved by Cheng Sui, one of the leading seal engravers of the Anhui School. The four inscribed characters, ' jiao lin jian ding ', mean 'appraised by Jiaolin', and have been executed with decisive and vigorous carving lines. These characters are rich in calligraphic interest for their rustic simplicity and skill. The name 'Jiaolin' was the alias of a famous collector of calligraphy and painting, Liang Qingbiao, who lived in the 17th century. This seal, then, might have been custom made for him.

Cheng Sui, the engraver, was a native of Anhui who lived in the 17th century, between the Ming(1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. After the fall of the Ming, he moved from Nanjing to Yangzhou . He was very well-read, and a versatile artist steeped in many disciplines, from landscape painting and poetry, to prose and calligraphy, particularly the study of stone and metal engraving. He was also an avid collector, and was able to appraise ancient paintings, books, bronzes and jades.

-

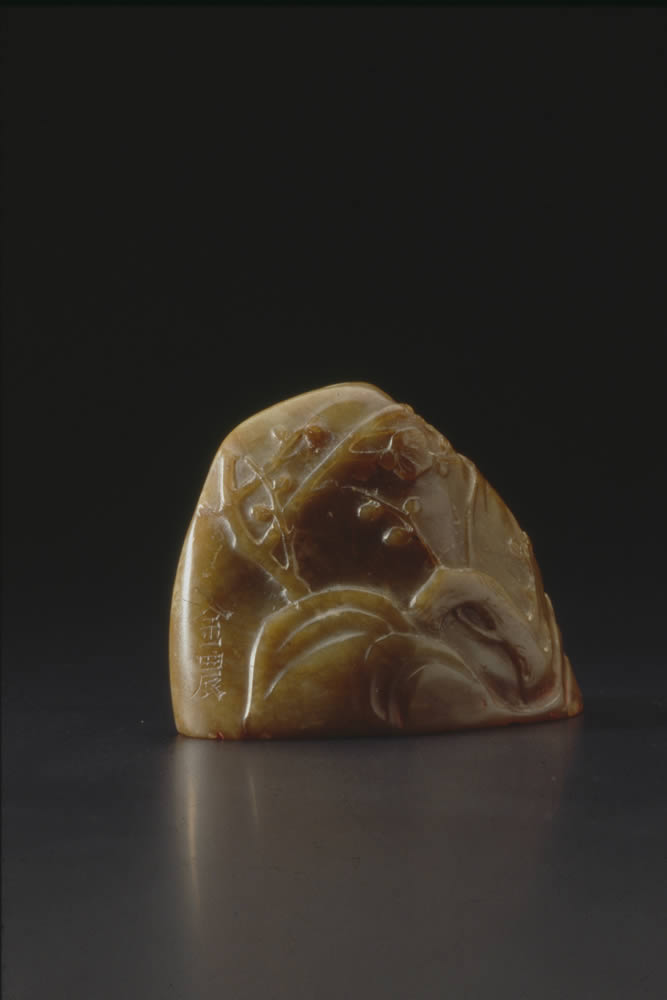

Oval seal with four incised characters

One of the three prominent stones used in carving, Qingtian stones were quarried from the mountain caves in Qingtian county of Zhejiang province. Extremely fine-grained, they have a hardness that permits deft and fluent movements of the carving knife. Qingtian stones usually appear monochrome and are thus often named after their colour — for example yellow, black or purple — although the majority of them are green.

The sides of this dark brown, semi-oval Qingtian stone seal carved by Jin Rong (1687–1764) are incised with beautifully arranged flowers, rocks and plants. The incised lines and designs are delicately rendered, reflecting Jin Rong's mastery in painting. The curved outline of the seal mark perfectly matches the irregular contours of the incised characters to convey a desolate and solitary ambience. These types of oval seals were popularly used by connoisseurs as certifying seals or as the introductory seals impressed on the yinshou (preamble or frontispiece) of a Chinese painting or calligraphy scroll.

A native of Hangzhou in Zhejiang province, Jin Nong, also known as Shoumen, literary name Dongxin, started learning the art of painting and writing at the age of fifty. In his later years, he resided in Yangzhou, where he earned a living by selling his paintings and calligraphy works. Excelling in poetry, calligraphy, painting and engraving, Jin was renowned as one of the "Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou".

-

Square seal with four incised characters

This marvellous stone seal successfully conveys a consistent message through the use of a pictorial image and engraved calligraphy. Vividly depicted on the top is a dragon's head carved in high relief and surrounded by an incised cloud pattern, while inscribed on one side is a poem describing a hermit who withdrew from society and its competitive nature to live in seclusion in Nanyang. The tenor of the poem is reinforced by the four incised characters on the base, " Nanyang buyi " — literally meaning an ordinary man in Nanyang, which refer to Zhu Geliang, a man of letters and great wisdom who had once lived in solitude in Wolonggang of Nanyang during the Three Kingdom periods (220–265) before later becoming the prime minister of the Kingdom of Shu.

Qi Huang (1863–1957), also known as Azhi and Pingsheng, was frequently referred to as Baishi, as he was a native of Baishi village in Xiangtan of Hunan province. In his youth he worked as a carpenter, earning the nicknames Muren and Mu jushi, but at the age of twenty-seven he began to study painting, calligraphy, poetry and seal engraving, and in his later years he resided in Beijing, where he earned a living by selling his seal engravings and paintings. Qi developed his own unique style based on his studies of the seal script prototypes of the Qin, Han and Wei dynasties (221–265) as well as exquisite models of other noted seal carvers such as Zhao Zhiqian (1829–1884) and Wu Changshuo (1844–1927). With his masterly technique in seal engraving, he manipulated the carving knife smoothly as if it was a Chinese brush, yet his works bear the hallmarks of naive and unpolished choppy lines created by straightforward gestures and a speedy rendering of the knife. Qi enjoyed a reputation equal to that of Deng Sanmu (1898–1963), a famous seal carver of the same period from Shanghai, and together they are known as "Northern Qi and Southern Deng ".

-

Rectangular seal with two characters carved in relief

Quarried in the village of Shoushan of Fuzhou in Fujian province, Shoushan stones feature a soft texture and lustrous appearance that makes them ideal for creating virtuoso carvings and marvellous works of art. Rectangular stone seals are often used for private rather than official purposes, and they are commonly inscribed with poetic verses and the names of art studios. They are also popular among connoisseurs as certifying seals or as the introductory seals impressed on the yinshou (preamble or frontispiece) of a Chinese painting or calligraphy scroll.

Exquisitely embellished with incised lotus and snipe, this stone seal demonstrates the masterly skill in painting of the carver Feng Kanghou. Rendered with remarkable fluency and delicacy, the two characters "You Mei" engraved in rounded relief at the base reveal that the seal was carved for Xu Youmei (active in early 20th century), the owner of a painting agency called Hongxue Xuan which was established in the 1930s.

A native of Panyu in Guangdong province, Feng Kanghou (1901–1983), original name Feng Qiang, also known as Laokang and Miaosou, learned seal engraving at the age of thirteen by studying the works of Huang Shiling (1849–1908) as well as from Liu Liu'an, from whom he also learned calligraphy. Devoting much of his lifetime's work to the study of inscriptions on ancient bronzes and stone tablets, Feng excelled in seal engraving and calligraphy and was particularly noted for his writing of seal scripts. He also studied painting under his uncle, Wen Qiqiu, and occasionally produced landscape and flower-and-bird paintings. In his later years, Feng resided in Hong Kong, where he continued to dedicate himself to artistic creation.

-

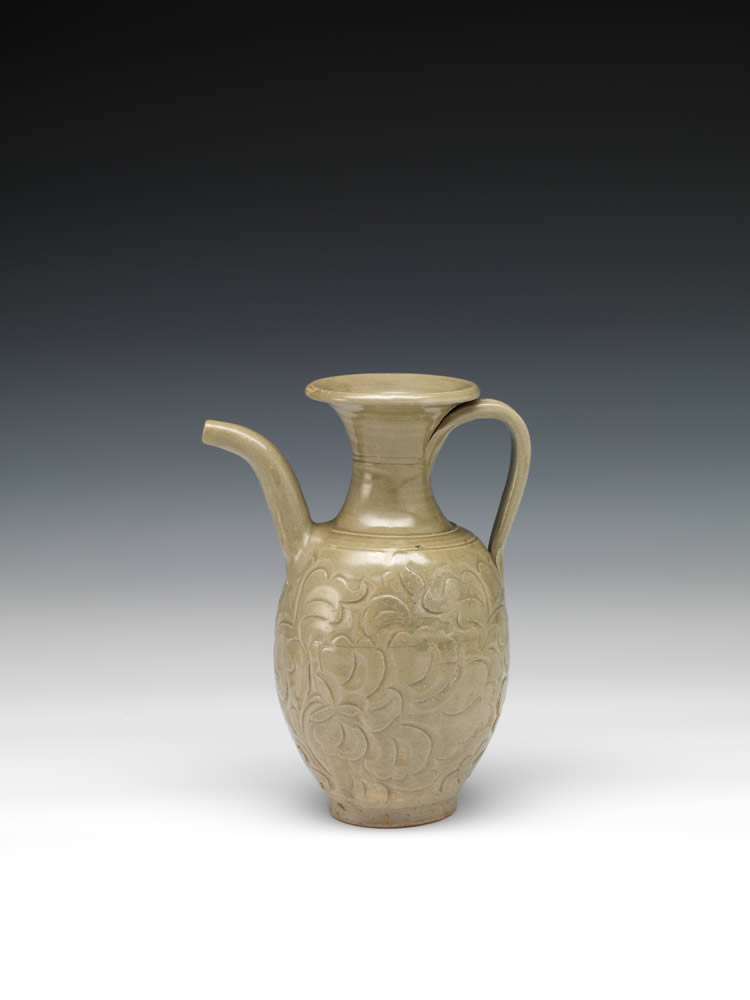

Ewer of oval shape with carved peony sprays design in celadon glaze, Yaozhou ware

The Yaozhou kilns, located in present-day Huangbaozhen in Tongchuan, Shaanxi province, had already produced a wide range of ceramics in black glaze, white glaze and celadon as early as the Tang dynasty (618–907), but it was in the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) that they produced one of China's classic celadon wares. The manufacture of this type of pottery reached its apogee in the second half of the 11th century, when these celadon wares were mainly decorated with carved or moulded designs.

This slender ovoid ewer has a light olive-green glaze with fine crackles. Traces of the wheel throwing are discernible on the interior and exterior walls down from the mouth to the slender-waisted trumpet neck. Extending from the neck to the body is a braided handle. The buff stoneware body is carved in low relief with an all-over design of peony sprays delineated with smooth, sharp lines to convey a sense of fluent motion and vitality.

"Whipped tea" was a method for preparing tea that was in vogue during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Boiling water was poured over the tea powder in the bowl, and the mixture was then whipped with a bamboo whisk to make a thick frothy brew. The long, curved spout of this ewer was an innovation at the time designed to produce a strong and controlled flow of water as it was poured onto the powdered tea.

-

Tea bowl with hare's-fur russet markings in black glaze, Jian ware

This Jian ware tea bowl is an example of the basic utensil used in tea contests in the Song dynasty (960–1279). The Jian kilns, located in present-day Suijizhen in Jianyang of Fujian province, mainly produced black-glazed tea bowls with dark brown bodies. The thick and lustrous black glaze of this tea bowl is marked with golden streaks, usually called "hare's-fur" markings, which are the fine, crystalline patterns formed during firing in the kiln.

Jian ware bowls were highly rated by Northern Song connoisseurs, as we can see from the Chalu , Daguan Chalun and other texts of the Song dynasty. At the tea contests that were very popular in this period, tea was first graded by colour. The colour to which contestants aspired was white, and this was achieved by adding boiling water to the bowl and then whipping the liquid to create a layer of white froth floating on the surface. Black-glazed Jian tea bowls were perfect for highlighting the rich white tea decoction: their thickly potted bodies retained the heat longer, while the depth of these bowls was also ideal for judging the contents. It is no wonder that the Song people who took part in tea competitions ranked Jian bowls above all others.

-

Teapot of eight-lobed shape with floral design inside reserved panels in wucai enamels in imitation of Japanese Kakiemon ware

This teapot is a rare Jingdezhen piece copying Japanese Kakiemon ware for the Western market. First introduced into Europe by the Dutch East India Company in the late 17th century, Japanese Kakiemon wares with their brilliant colours and attractive patterns soon gained wide popularity in the West. Produced in Japan's Arita province, this kind of Japanese porcelain grabbed large shares of the export market when the Ming dynasty fell in 1644 and proceeded to exert a considerable influence on European tastes. It was not until the Kangxi period (1662–1722) of the Qing dynasty that China managed to re-establish its porcelain export trade.

This teapot decorated in wucai style was made during the Kangxi period from the late 17th to the early 18th century. It has an eight-lobed melon form with a low domed lid, while the body is outlined in underglaze blue with eight vertical panels. Embellished in each panel are floral stems of mallow, pomegranate or chrysanthemum in a combination of blue with green, yellow and red enamels. The spout and the handle are decorated with lotus foliage scroll in green.

-

Twelve cups with representing flowers of the months in wucai enamels

-

Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662–1722)

-

Mark of Kangxi in underglaze blue

-

Height : 5 cm Diameter : 6.5 cm

-

C81.245

The thinly-potted cups are painted in an elegant and delicate manner with flowering plants and trees each characterising a particular month of the year. Outline drawing is generally in black and various minor plants, rocks and water are represented in underglaze blue or enamels. Each cups bears on the reverse side a poem in blue, followed in each case (except the twelfth) by the seal: shang (to appreciate). Divergences in style or in quality suggest that the first, second, fourth and twelfth cups are from different sets and may be from a later period. The decoration of these rare cups is discussed in a leaflet issued by the museum in 1989 to accompany the exhibition, "Floral Deities", where the subjects are identified and associated with their appropriate months in the following order. It should be remarked that different interpretations have at times been proposed for certain flowers and for the overall order.

-

Teapot with the three friends of winter in doucai enamels

-

Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period (1723–1735)

-

Mark of Yongzheng in underglaze blue

-

Height:13.6 cm, Width:19 cm

-

C81.115

Sturdy plants that can endure and survive well in cold weather, pine, bamboo and prunus are known in China as the "Three Friends of Winter". The pine symbolizes longevity and persistence, bamboo implies righteousness and decency, while prunus represents purity and virtue. The motif of the "Three Friends" has always been widely adopted in Chinese decorative arts because of its symbolic meaning, and it features strongly in this oviform pot with a rounded top. The pot's large loop handle and the curved spout correspond harmoniously with the flattened ring knob of the fitted lid to convey a fluent and rhythmic motion. A six-character mark in archaic seal script reading "Da Qing Yongzheng nian zhi" is written in underglaze blue in three columns on the recessed base. This pot originally formed a pair with one held by the Percival David Foundation in London.

The decorative method used on this pot is known as doucai, which is a combination of underglaze and overglaze decorations. The decorative motifs on both sides of the porcelain would be delicately outlined in underglaze blue, then a layer of transparent glaze would be applied before the vessel was fired at 1200°C. Overglaze enamels in green, light and deep red and aubergine were subsequently added to the delineated areas before the pot was fired for a second time at around 800°C to achieve a vivid design with rich tonal gradations.

-

Covered teacup and saucer with calligraphic inscriptions in underglaze blue

-

Qing dynasty (early 19th century)

-

Mark of Man tang fu ji in underglaze blue

-

Height (cup) : 5.2 cm Diameter : 10 cm, Height (saucer) : 2.7 cm Diameter : 13.4 cm

-

C81.250

Covered bowls were first introduced in the Kangxi period (1662–1722) of the Qing dynasty. Their flared mouths make them easy to fill with water and to pour tea into smaller cups for drinking. Some tea drinkers take full advantage of the covered bowl to sip tea directly from it by holding the bowl and the saucer in one hand and lifting the cover with the other to gently blow any tea leaves away. Compared with teapots, covered bowls offer better heat dissipation and they are thus widely used for brewing green or scented tea.

This covered bowl consists of a cover, a bowl and a stand, which together form a functional tea ware set. Transcribed on the outside of the bowl and cover and on the inside of the stand are Tang dynasty poems expressing sentimental feelings about the passing of time and melancholic moments in life; the neatly written calligraphy forms a unique pattern on the vessel. The mark of the shop that produced or sold the set, "man tang fu ji", is written on the top of the cover and repeated on the bases of the bowl and the saucer. The rims are bound in copper to protect the sides of the eggshell-thin porcelain.

-

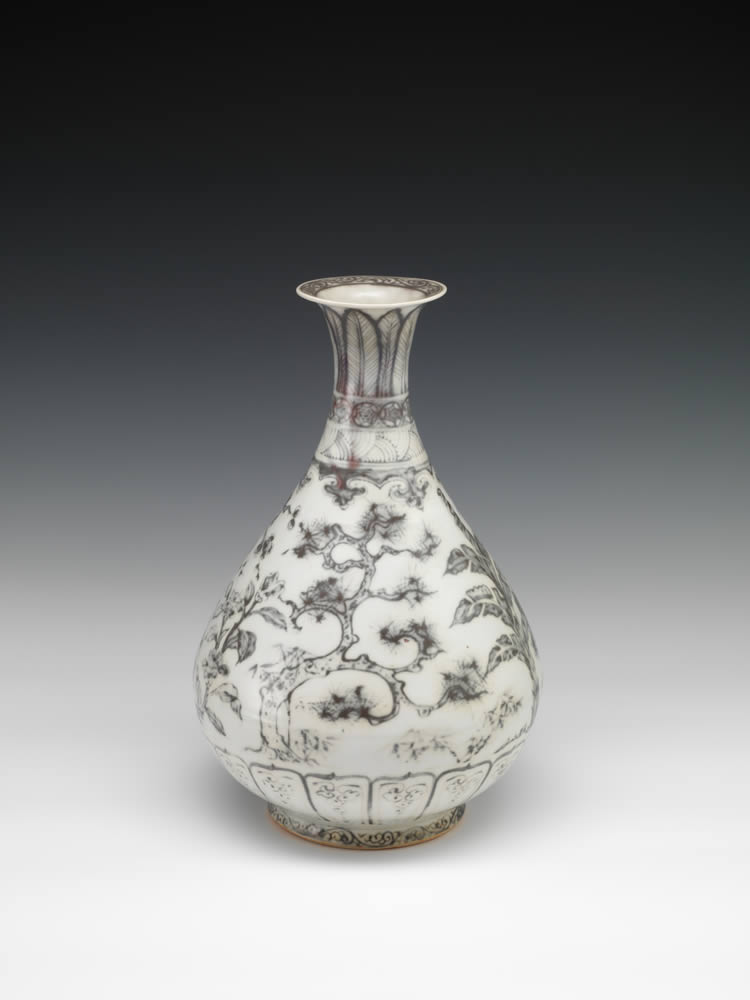

Pear-shaped vase painted in underglaze red with the three friends of winter

-

Ming dynasty, Hongwu period (1368–1398)

-

Height: 32cm, Diameter (mouth): 8.5 cm, Diameter (belly): 20.7 cm, Diameter (foot): 11.6 cm

-

C94.73

This pear-shaped vase was made in three parts and joined horizontally. Starting from the mouth with a classic scroll design and then moving down to the neck are three bands of patterns respectively delineated with banana leaves, a linked "cash" motif and stylized waves. Painted around the body in underglaze red is the "Three Friends" design — pine, bamboo and prunus — in a continuous garden scene, with banana plant and camellia filling in the empty spaces. Below this main design and around the foot are two bands decorated with lotus panels and classic scrolls. The spatial arrangement of the decoration reveals a transitional style between early pieces intended for export, as exemplified by the large dishes in Near Eastern collections that feature a very crowded, compartmentalized décor, and those to be found in the 15th century that reflect a thoroughly Chinese taste.

The decoration of this piece was painted in underglaze red derived from copper. A layer of transparent glaze would have been applied before the vessel was fired at a high temperature. Copper oxide proved a very volatile material, and the chances of misfiring were quite high, with the result that many pieces such as this one turned out greyish or mud brown in colour. This difficulty explains why good underglaze red pieces are rare.

-

Flask painted in underglaze blue with dragons

-

Ming dynasty Yongle period (1403–1424)

-

Height: 45 cm, Diameter (mouth): 8 cm, Width: 35 cm

-

C94.74

The development of underglaze blue ware reached its apogee during the Yongle and Xuande periods (1426–1435), an era in the Ming dynasty known for their splendid achievements. The cobalt used as a colorant for the underglaze blue decoration was imported in this period from Persia, hence its name "sumani qing" (Mohammedan blue). The wares produced were characterized by their rich blue decorations and the "heaped and piled" effect that emerged in places where the pigment condensed. The pigment was often so thick that it broke through the glaze surface and oxidized almost to black. The glazed surface was often uneven, resulting in an "orange peel" appearance.

With a white glaze that has a slight bluish tinge and a form that originated in the Yongle period (1403–1424) of the Ming dynasty, this type of compressed globular flask with a straight neck flaring at the mouth was used as a container for water or wine. A large three-clawed dragon dominates the body of the flask, with cloud forms filling out the design. Below the rim of the mouth is a floral scroll, while a band of three foliate scrolls on top of each other encircles the neck. The painted design reveals spontaneous brush strokes of a robust quality.

Uncommon during the Yongle period, the practice of applying reign marks on articles for imperial use became fashionable in the Xuande period. A piece of this size, quality and importance without a reign mark would thus probably have been made earlier than the Xuande period.

-

Palace bowl painted with scrolling vines and melons in underglaze blue

-

period of Chenghua (1465–1487), Ming dynasty

-

Mark of Chenghua (1465–1487), Ming dynasty

-

Height: 6.8 cm, Diameter (mouth): 15.4 cm, Diameter (foot): 5.3 cm

-

C94.78

During the Chenghua period (1465–1487) of the Ming dynasty, porcelain ware tended to feature a thin, refined and translucent body, while the firing technique was improved to produce a thick and even glaze without the "orange peel" undulations of earlier times. The underglaze blue decoration utilized a cobalt blue called pingdeng qing or potang qing made locally in China's Jiangxi province. The blue decoration was evenly applied and had a soft, greyish-blue tone under a slightly opaque glaze, with the outlines often appearing a little blurred. While some Chinese connoisseurs prefer the more robust qualities of the earlier Yongle and Xuande wares, there is no doubt that the art of porcelain making reached a peak of technical perfection and refinement in the Chenghua period in the late 15th century.

This bowl of elegant form has gently curved sides, a subtle flare at the rim and a low ring foot. It is painted with three groups of scrolling vines and melons on the exterior, but the interior is kept plain. A six-character mark, "Da Ming Chenghua nian zhi", is written in underglaze blue in two columns of regular script within double circles on the slightly concave base. This bowl belongs to a group of blue-and-white bowls from the Chenghua period: of extremely fine quality and painted with floral scrolls or figures in a landscape, they are usually referred to as "palace bowls", as they were intended for imperial use.

-

Teapot with tea-serving scene and calligraphy inside reserved panels in fencai enamels on yellow ground

-

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736–1795)

-

Mark of Qianlong in underglaze blue

-

Height : 12.6 cm Width : 17 cm

-

C1981.0073

Emperor Qianlong (1736–1795) was a fervent tea lover and also adored literature. He had composed about 200 poems on tea. This teapot with exquisite enamel decoration was produced for imperial use. Painted on one side in a reserved panel is a man being served tea in an open pavilion in a garden. On the other side is a poem entitled "Watching Tea-picking at the Cool Spring Pavilion". The poem was written when Emperor Qianlong visited Hangzhou where he was inspired by the tea makers who worked very hard in producing longjing tea leaves:

Tea leaves are tender before the Ching Ming Festival and become mature afterward.

Longjing tea of the West Lake is the most famous. If you happen to visit, have a tasting and learn how to make it. Boys in the village pick the leaves, filling baskets of Queshe (bird's tongue) and Yingzhua (eagle's claw). The stove on the ground is set at low heat to process the continuous flow of tea leaves, fried on a dry cauldron in circular movement. The processing is done meticulously in a precise order, which takes a lot of hard work. Sadly, the tea is unknown to tea connoisseurs such as Wang Su, and The Classic of Tea by Lu Yu was too specific as a study. Although I enjoy the tea, I never asked for the very best. I was afraid that my tiniest request could open up a quest for peculiar tea that would burden tea-pickers. Specially made for his majesty Qianlong.

The rest of the teapot surface is painted with floral scrollwork on a lemon yellow ground; the inside of the pot and lid are in light turquoise enamel.

-

Washer, Ru ware

The ceramic wares from the kilns of Ru, Ding, Ge, Jun and Guan of the Song dynasty are traditionally considered the best in China. Ru ware produced during the early 12th century are extremely rare today, with less than 70 works extant . Accompanying this washer is a document written by a gentleman called Chen Yuanhui, which dates to be one autumn day in the Bingwu year of the Guangxu period (1906). According to it, Chen's father Chen Rui'an acquired the washer in Liulichang in Beijing. Originally it carried an inscription of a poem by Emperor Qianlong, written in the Jihai year (1779), on the base, which reads:

At Ruzhou during the Song Dynasty, a celadon ware used agate powder as its glaze. No like artifice Jingdezhen could devise, with an emerald-like blue hue floating on the surface.

Chen Rui'an had the inscription removed for fear that the possession of a piece from the Qing imperial collection might prove to be incriminating. Similar collections can be found in the Taipei Palace Museum and the David Foundation of Chinese Art in London.

-

Teapot of gourd shape

-

Chen Hongshou (1768–1822), Yang Pengnian (1796–1820)

-

Early 19th century

-

Seals of (Yang) Pengnian; Jihu, Inscription by Mansheng (Chen Hongshou)

-

Height : 7.9 cm Width : 10.8 cm

-

C81.401

The production of Yixing tea ware experienced a revival at the beginning of the 19th century, which emerged in tandem with the change in intellectual tastes. At that time, scholars liked to demonstrate their literary talents through painting, calligraphy and seal engraving on the plain, undecorated surfaces of teapots of simple shapes. Inscriptions of poetry, epigrammatic quotes and religious sayings are commonly found on the body of teapots as a result of collaboration between potters and scholars. The teapots therefore carry marks of both the potter and the owner's studio.

Chen Hongshou (1768–1822), alias Zigong and with the sobriquet Mansheng, was an eminent scholar and artist from the Jiangnan region, active during the late Qianlong to early Daoguang periods. Chen is recorded as having designed eighteen teapot styles when he served as the Magistrate of Liyang (a neighbouring county of Yixing in Jiangsu province) and commissioned the two leading potters of the time, Yang Pengnian (1796–1820) and Shao Erquan (active in the early to mid-19th century) to make teapots. The teapots with the seal mark "Pengnian" under the handle, "Amantuo Shi" (name of Chen Mansheng's studio) under the lid, and decorated with the poetry and signature of Chen Mansheng on the body, are known as "Mansheng teapots".

Since the Ming dynasty, people preferred to prepare tea by steeping loose tea leaves in a teapot. This was called the "steeping method". Apart from glazed teapots made of porcelain, those teapots made of zisha from Yixing of the Jiangxu province were most treasured by the tea epicures in the Qing dynasty. The minute porosity yet impermeable nature of Yixing teapots makes their clay bodies highly absorbent. After long periods of use, the tea-stained interior of the teapots would enrich the flavour of the tea infusion by producing a stronger taste. The Yixing teapots were also cherished by the literati for their elegant designs and simple forms, which matched the aesthetic tastes associated with tea drinking at that time.

-

Teapot of compressed round shape with tall well-railing overhead handle

-

Gu Jingzhou (1915–1996), Han Meilin (1936–)

-

Dated winter of dingmao year (1987)

-

Seals of Gu Jingzhou; Jingzhou; Zhou; Lixia (Han) Meilin

-

Height : 14.8 cm Width : 14.2 cm

-

C88.33

One of the most outstanding Yixing potters of the late 20th century, Gu Jingzhou (1915–1996) was born into a family of potters in the village of Shangyuan in Chuanbu, Yixing, in Jiangsu province. He learned pottery from his grandmother and was already ranked among the eminent potters of his time by the age of twenty. Gu was one of the pioneering forces in the establishment of the Yixing Purple Clay Factory in 1955, where he devoted much effort to training the younger generation. He was awarded the title of National Craft Master in 1978 by the central government and honoured as a Master in Arts and Crafts of National Order in 1988.

Gu produced this exquisite work in collaboration with Han Meilin (born in 1936), a famous designer of Yixing tea ware. Gu developed his unique style by combining traditional techniques with innovative ideas. With its excellent craftsmanship, the work exhibits a fine articulation of lines and proportion. The form of the teapot is succinct, elegant and perfectly balanced, fully expressing the characteristic qualities of Yixing pottery.

Gu's works repeatedly won gold and silver medal awards at national exhibitions and competitions, and they have frequently been selected to be presented as commemorative gifts on international missions. Highly renowned for his skill, Gu was known as "the great master" and "the giant of Yixing pottery".

Web Content Display

Web Content Display