Web Content Display

Web Content Display

China Trade Art

The very first works of art whose acquisition was to lay the foundation for the Hong Kong Museum of Art and its collections were China trade art reflecting the life, customs and landscapes of China in the preceding centuries. Long before the Museum itself was established, two benevolent businessmen, Sir Paul Chater and Sir Robert Ho Tung, donated their private art collections to the Hong Kong government, which thus came into the possession of a large quantity of paintings, photographs and maps depicting the Pearl River Delta and scenes along China's coastline in the 18th and 19th centuries. Later, the government purchased a number of China trade paintings that had been collected by Wyndham Law and Geoffrey Sayer. The custodianship of these works was then handed over to the City Hall Art Gallery and Museum, which opened in 1962 and was later to become the Hong Kong Museum of Art. Building on this core, the Museum continues to acquire relevant works for its collection, which, with over 1,300 sets of pictorial objects now in its collection, has not only become an invaluable resource for historical study but also bears witness to the artistic achievements of a particular group of painters.

Many of the painters of these China trade art were Western artists who came to China in the 18th and 19th century to trade or to tour. During their sojourns in Hong Kong, Macao and Canton (today's Guangzhou), they churned out many drawings, watercolours and oil paintings depicting scenes of the daily life and landscape they encountered. After returning to their home countries, some reproduced their works in various types of prints, and it was through their ‘travelogues' that China, the Middle Kingdom at the heart of the exotic Far East, was introduced to the Western world.

Foreign traders and artists brought Western painting techniques with them to China, which several native Chinese artists took the time to master. Cannily spotting an opportunity, they set up art studios in Canton and Hong Kong where they mass-produced genre scenes of treaty ports, portraits and still lifes, which were then sold to foreign tradesmen as souvenirs. China trade paintings found a huge market at that time, but with the growing popularity of photography in the late 19th century, they lost their pre-eminent place and eventually became part of the history that they were themselves intended to portray.

The works selected here highlight both the meticulous style of Chinese artists and the impassioned brushstrokes of Western painters. But perhaps what the visitor will find more striking is the simplicity of Hong Kong before the British rule in 1841, perhaps more attractive the romantic appeal of Macao's Praya Grande during the previous century, more impressive the past prosperity of the city of Canton. Through these images that are by turns fascinating and yet vaguely familiar, the China Trade Art Collection offers a rare insight into our distant past.

-

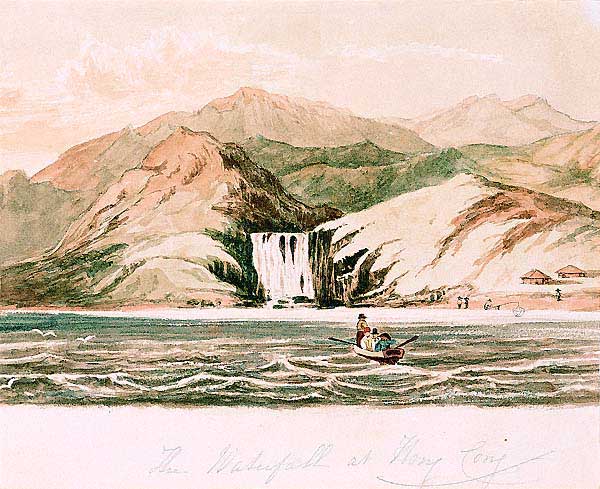

Waterfall at Aberdeen, Hong Kong

-

William Havell (1782 – 1857) (attri.)

-

ca. 1816

-

Watercolour on paper

-

10.5 x 16 cm

Waterfall at Aberdeen is the earliest work in the Museum's collection depicting Hong Kong's landscape. Hong Kong was a small and desolate island in 1816 when Lord Amherst led a trade mission from Britain to China. The ships of the Amherst Mission anchored in Hong Kong waters on their journey to Beijing in order to stock up on supplies of fresh water. The painting, attributed to the mission's artist William Havell, depicts the ship's crew setting out towards the waterfall, which is today believed to be located at the Waterfall Park at Aberdeen. -

-

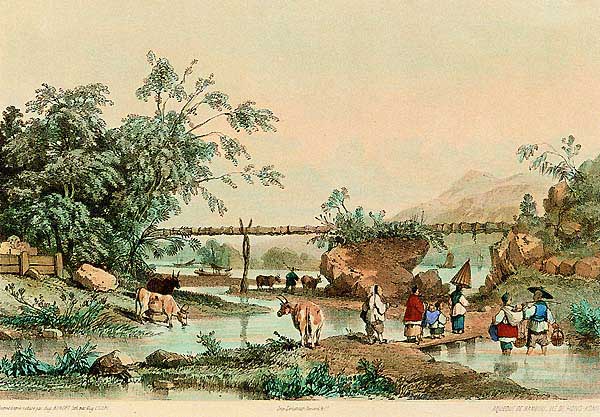

Bamboo aqueduct, Hong Kong

-

Auguste Borget (1808 – 1877) (drawn); Eugene Ciceri (1813 – 1890) (lithographed)

-

1838

-

Coloured lithograph

-

19 x 28.5 cm

This colour lithograph depicts agricultural land allegedly in the Wong Nai Chung Valley. In the centre, a bamboo pipe connected to a little canal on the summit forms an aqueduct conveying water across the valley to fertilise the land, and the picture thus reflects Chinese wisdom in solving daily problems. -

-

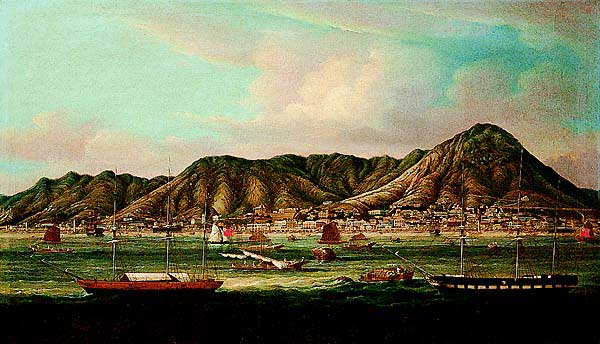

Victoria City

-

Youqua (act. 1840 – 1870s) (attri.)

-

1854

-

Oil on canvas

-

57 x 100 cm

This fine oil painting is an accurate portrayal of the city of Victoria and its harbour as they appeared a century and a half ago. As well as presenting a record of the locations of buildings, the painting delineates their forms in meticulous detail: Government House, then under construction but completed in 1855, features a temporary thatched roof, while to the east is St. John's Cathedral, which was finished in 1849. -

-

British naval detachment encamped at Kowloon

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1900

-

Oil on canvas

-

44.4 x 58.1 cm

-

Donated by Mr Gerald Godfrey

Believed to have been executed by an amateur military officer, this oil painting depicts a British naval detachment encamped at Kowloon, possibly on its way to northern China to fight the Boxers. The dark forest, white tents and the red flag present a strong contrast of colours. -

-

Portrait of Macao sampan girl

-

George Chinnery (1774 – 1852)

-

1825 – 1852

-

Watercolour on paper

-

12.5 x 9.5 cm

The Tanka boat girl of Macao was one of the favourite subjects of British artist George Chinnery. The model he used in this watercolour is variously referred to as Ah You, Ah So or Ah Loi, but the real identity of the girl is not known. -

-

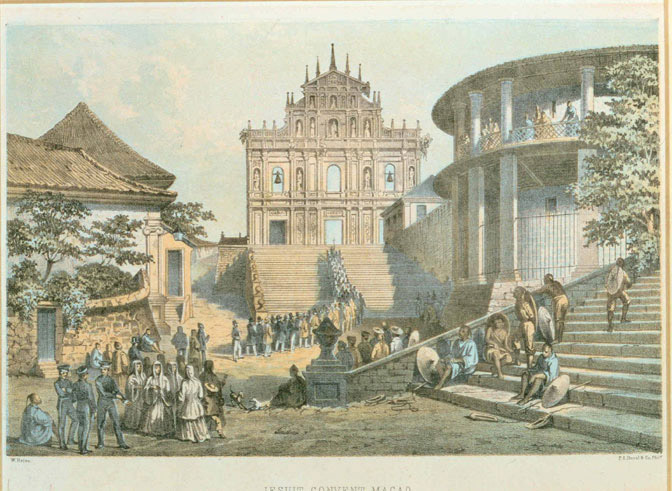

The facade of St. Paul's Church, Macao

-

William Heine (drawn)

-

ca. 1845

-

Coloured lithograph

-

15 x 22.5 cm

The grand architectural feature that forms the central focus of this lithograph is the ruins of St. Paul's Church, known as the Sao-Paulo fasade, which was all that was left standing after a fire broke out in 1835 and destroyed the rest of the church. Also called "The Jesuit Convent", the lithograph presents a procession celebrating a ceremony of the Catholic Church and watched by groups of passers-by. -

-

View of Praya Grande, Macao

-

Edward Hildebrandt (1818 – 1869) (drawn)

-

1863

-

Coloured lithograph

-

25 x 38 cm

Adopting a reserved palette with sienna and a light touch of blue for the sky and sea, this watercolour by German artist Edward Hildebrandt depicts the view of the Praya Grande from the south in the middle of the 19th century. The magnificent Western building along the long curving bank and the foreign ships moored in the harbour convey a very European atmosphere on this Chinese peninsula. -

-

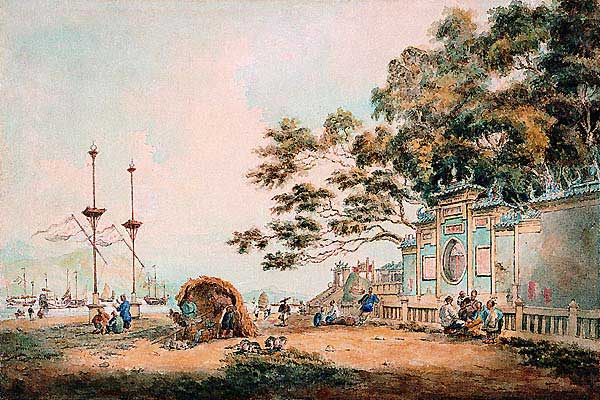

Ma Kok Temple, Macao

-

Marciano António Baptista (1826 – 1896)

-

Mid 19th century

-

Watercolour on paper

-

30.5 x 45.5 cm

Located on the shore of the inner harbour, the ancient Mak Kok Temple was built during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) and dedicated by the fishermen who built it to Tin Hau, the Goddess of the Sea to whom they owed their livelihood. The open ground outside the temple naturally became a meeting place for fisher folk and an obvious attraction for Portuguese artist Marciano António Baptista, who depicts a lively scene with a blacksmith, women, children and some pigs wandering around. -

-

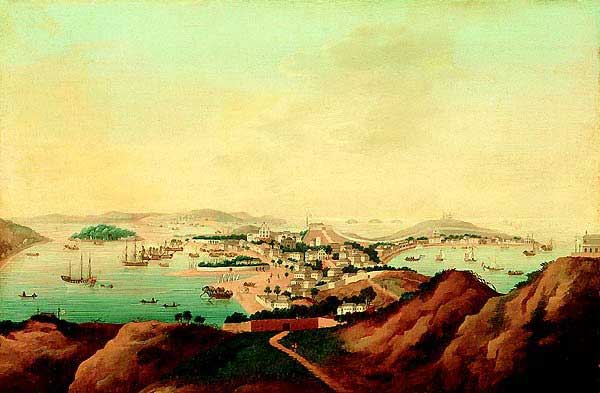

Central Macao from Penha Hill

-

Anonymous

-

Late 18th century

-

Oil on canvas

-

35.5 x 54.3 cm

-

Donated by Sir Robert Ho Tung

This oil on canvas, of unknown origin, presents a view of late 18th century Macao looking north from Penha Hill. On the left are the Inner Harbour and Green Island, while Guia Hill and the Praya Grande are on the right, with Monte Fort in the centre and St. Dominic's Church directly in front of it. St. Paul's Church, which later burnt down in 1835, can be seen to the left of Monte Fort. -

-

Bocca Tigris

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1860

-

Oil on canvas

-

41.4 x 74.4 cm

Bocca Tigris, which means "Tiger's Mouth", was a narrow spot at the estuary of the Pearl River that Western ships had to pass through to reach Guangzhou. The Qing government guarded the entrance to the river with numerous forts and batteries. Permits were examined here to ensure that foreign ships had settled all duties and taxes at the Whampoa customs before they departed. Although the artist is not known, this oil on canvas is composed in a style and with a perspective traditionally associated with Western painting. -

-

The Whampoa anchorage

-

Youqua (act. 1840 – 1880s) (attri.)

-

ca. 1850

-

Oil on canvas

-

41.4 x 73 cm

-

Donated by Sir Robert Ho Tung

From 1757 to 1840, Guangzhou, with Whampoa Island as her outer harbour, was the only port open to foreign trade in China. Ships moored here to measure the hold, pay taxes and unload their cargoes, which would then be transported by sampan to the city some thirty miles away. Many shipyards and godowns sprung up along the shores of Whampoa Island to provide services for these ships. In this work attributed to Youqua, a trade painter who excelled at harbour scenes, the fine delineation of the boats and buildings is executed by particularly meticulous brushstrokes. -

-

Foreign factories in Guangzhou

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1784 – 1785

-

Gouache on silk

-

43.5 x 71 cm

-

Donated by Sir Robert Ho Tung

Believed to be the work of a Chinese artist, this gouache on silk depicts a view of factory buildings facing the river in Guangzhou. Presented in a neatly arranged row, these Western-style buildings are mostly two-storey-high: the top floor would serve as living quarters, while the ground floor would be used as an office or storage area. Small boats can be seen moored along the bank: all foreign cargo ships had to be loaded and unloaded using these barges. -

-

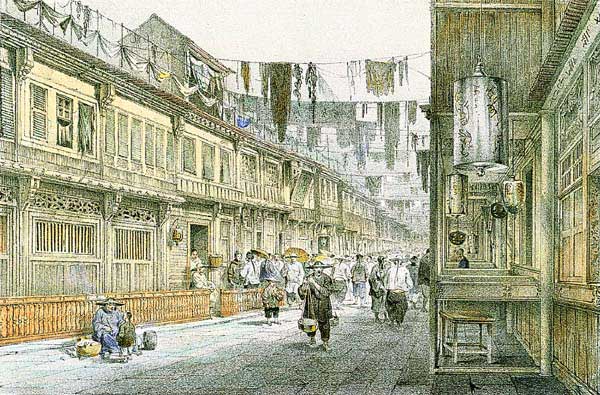

New China Street

-

Barthelemy Lauvergne (1805 – 1875) (drawn); Bichebois (lithographed)

-

19th century

-

Coloured lithograph

-

19.3 x 29.5 cm

In the 19th century, tight restrictions were imposed on Western traders in Guangzhou, and they were only allowed to reside and carry out their trading activities in a specially designated area known as the Foreign Factories. Located between the Danish and the Spanish Factories, New China Street was full of shops that sold all kinds of goods and was also home to the studio of the famous trade painter Tingqua, which was housed at number 16. -

-

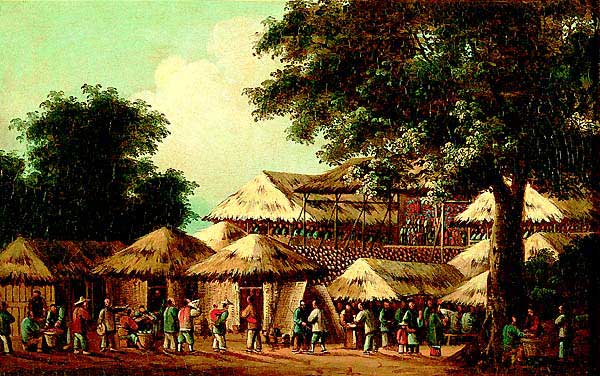

A Cantonese opera scene

-

Anonymous

-

19th century

-

Oil on canvas

-

28 x 44 cm

-

Donated by Mr and Mrs Anthony J. Hardy

Opera was traditionally performed at Chinese festivals and ceremonies, and a market would be set up at the same time next to the opera site. Presenting the scene at one of these occasions, this oil painting depicts various activities at a market in the foreground, while an opera performance can be seen in the middle to the right. -

-

A Chinese lady

-

Anonymous

-

Early 19th century

-

Oil on canvas

-

68.6 x 51.3 cm

One of the most striking features of this portrait of a typical Chinese beauty is her pale complexion, characteristic of elegant and leisured ladies of her day. She has an oval face, with arch eyebrows and an obviously fastidious dress, while her valuable jewelleries complement and accentuate her beauty. Although the artist is unknown, the impact of traditional Western figure painting can clearly be discerned in this oil on canvas. -

-

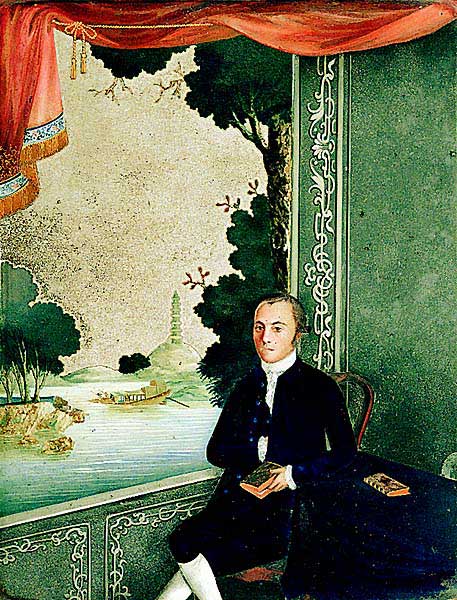

Portrait of a Western merchant on the China coast

-

Spoilum (act. 1770 – 1805)

-

Late 18th century

-

Reverse glass painting

-

25.9 x 20.6 cm

While they were trading in Guangzhou, many Western merchants commissioned portraits of themselves from Chinese painters. This one is a glass painting by a Cantonese artist, active between 1770 and 1805, called Spoilum. Executed in oil on the back of a glass panel and viewed from the front, glass paintings emerged in Europe as early as the 15th century. The red curtains, Chinese pagoda and fishing boats are common motifs in glass paintings of this period. -

-

Self-portrait of Lamqua

-

Lamqua (act. 1825 – 1860)

-

1853 – 1854

-

Oil on canvas

-

30.5 x 24.5 cm

An inscription on the back of the frame of this self-portrait states: "Lamqua / Aged 52 / Painted by himself / Canton 1853" (Dated 1854 in Chinese, a discrepancy awaiting further research). Lamqua was very famous in mid 19th century Guangzhou for his outstanding skill at oil painting and in particular the European-style of realistic figurative composition. Many of his paintings were intended for export. -

-

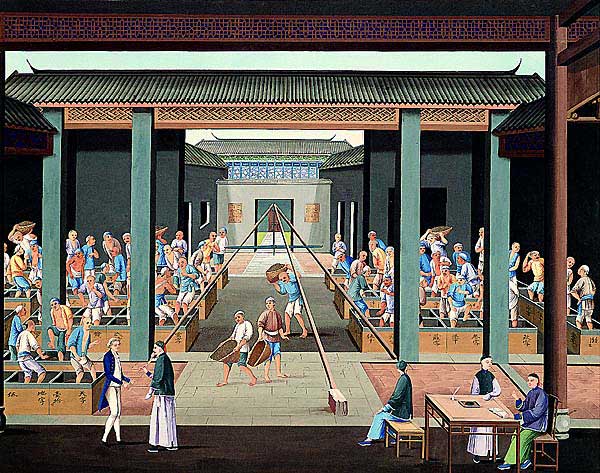

Production of tea: Packing tea for export

-

Anonymous

-

19th century

-

Gouache on paper

-

39.5 x 49 cm

From the middle of the 18th century to the eve of the Opium War, Guangzhou was the only port in China open for foreign trade and, as a result, all sorts of goods for import and export could be found here. Of all the Chinese export goods, tea was the foremost commodity. Grown and picked in Fujian province, the precious plant was transported by river to Guangzhou, where it was packed before being shipped overseas. This picture presents a typical tea-packing scene: at the rear, tea is being trampled down into chests, which are then weighed on the tripod in the centre; in the foreground to the left, a Chinese supplier and a Western merchant discuss final arrangements before shipment. -

-

A bouquet of flowers

-

Sunqua (act. 1830s – 1870s)

-

1830s

-

Gouache on pith paper

-

18 x 29.5 cm

This still life is a work by Sunqua, one of the most prominent trade painters in Canton of his day. Active from 1830 to 1870s, he specialised in oil paintings, and his favourite subjects were ships and scenes of trading ports. Despite the use of Western art medium and the minimal application of chiaroscuro to be observed here, the meticulous treatment of the subject, the infusive pigmentation and the thick palette all show the retention of Chinese painting styles and techniques. -

-

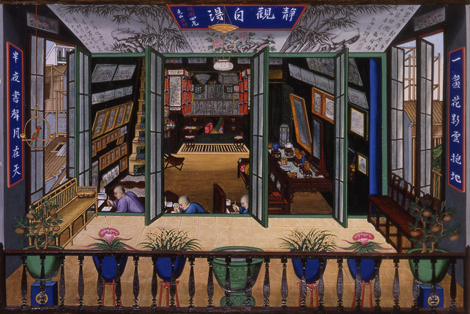

The studio of Tingqua

-

Tingqua (active 1840 – 1870s)

-

Mid 19th century

-

Gouache on paper

-

17.5 x 26.5 cm

The picture depicts the interior of the famous studio of Tingqua, whose Chinese name was "Guan Lianchang". He was one of the most celebrated Chinese export artists at the time. His watercolours in the bird-and-flower genre, port scenes and interiors were in popular demand. The studio was located at 16 New China Street in Canton. It was frequented by westerners who desired works that epitomized a slice of China, such as the rows of China trade pictures seen here hanging on the walls.

To fill the numerous orders, it was common for an established artist to employ other painters and apprentices to help. Seen here are three such helpers working by the windows. It is also interesting to note that although the works produced are in western style, the painters are holding their brushes in the traditional Chinese manner. -

-

British officers greeting Chinese mandarins

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1843

-

Watercolour on paper

-

29 x 39.5 cm

This watercolour painting has great historical significance. Despite an inscription in English at the bottom left corner reading “Hong Kong in 1841”, the work most probably depicts the official visit of the High Imperial Commissioner, Qiying (or “Keying”), in June 1843 to the then government house. He is met by Sir Henry Pottinger.

In the foreground is the entourage. A Chinese official, dressed in a Manchu court robe, is stepping out of a sedan chair. Standing in wait at the side is a foreign official in formal attire, and another foreign official at the top of the stairs is about to greet his guest. It is a very grand occasion. -

-

Guangzhou foreign factories on fire: Beginning

-

Anonymous

-

1822

-

Oil on canvas

-

27.5 x 38 cm

-

Donated by Sir Robert Ho Tung

On the night of 1 November 1822, a fire broke out in the neighbourhood of the Foreign Factories in Canton. It spread and engulfed the Foreign Factories, and was not put out until the next day. After the fire, the whole factory area had to be rebuilt.

This is the first of an oil painting series describing the incident, and it shows the outbreak of the fire. Here, tongues of flames are rising from the buildings behind the Foreign Factories. The people holding lanterns are those who have rushed here to help. Some arrive with buckets of water in the hope of putting out the fire. The sampan folks, standing on their boats, are also looking anxiously on. The artist has cleverly used gloomy colour tones to create the sense of gloom. The dark evening sky, the cold moon, the crimson tongues of flames and the thick smoke imbue a sense of urgency and highlight the gravity of the drama. -

-

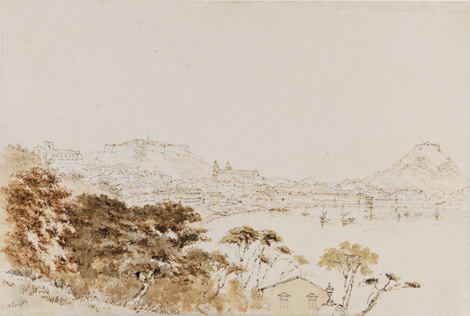

Extensive view of Macao from Penha Hill

-

Dr Thomas Boswall Watson (1815 – 1860)

-

1852

-

Pencil and brown ink and watercolour on paper

-

21 x 31.5 cm

The Scottish physician Dr Thomas Watson (1815 – 1860) has rendered a poetic touch to this scenic view of the Praya Grande by successfully capturing the ambience of the Mediterranean that so many of his contemporaries would have appreciated. Lining this handsome, curved esplanade are luxurious houses in European style. In the 19th century, the praya represented the best of Macao and was a typical theme of Macao landscape painting. In those days, when foreign merchants were not allowed to stay in Canton beyond the winter trading season, Macao was where they would reside, some with their families which were strictly forbidden entry to Canton or the foreign factories settlement. Over time, Macao became the home base of many large trading houses. All that changed when Hong Kong was ceded to the British, and foreign traders moved to the young and budding trading port.

Dr Watson settled in Macao in 1845. He was a well-known friend and allegedly a pupil of George Chinnery, the most sought after Western professional artist on the China coast. Chinnery left Britain in 1802 at the age of 28 for India, before settling in Macao in 1825. His style had a great influence on the amateur and professional artists in the region, and one of them was Dr Watson. When Chinnery died, Dr Watson was at his bedside and helped sort out his remaining papers and pictures. -

-

A Chinese sampan girl

-

George Chinnery (1774 – 1852)

-

ca. 1852

-

Oil on canvas

-

28 x 23.8 cm

Many of George Chinnery's works are about Chinese sampan girls. Alloy and Assor were the two models he used most. Many of his sampan girls have a full figure, with a sweet smile and amicable looks, as seen here in this painting. Portraits of this type form an important part of his oeuvre.

The girl in the painting wears Tanka clothes and a rattan hat, holding a scarf in her hand. Chinnery's signature elements are omnipresent in this figure painting: the quick but sure brushwork; his favourite device of using dashing vermillion in the cheeks and full lips; the use of shadows under the arm and between the fingers; as well as the graceful pose that turns this girl of the working class into an idealized nymph. -

-

The Chinese junk, Keying

-

Anonymous (drawn); Rock Brothers and Payne (published)

-

1848

-

Coloured aquatint

-

26.3 x 34 cm

-

Donated by Sir Paul Chater

The junk in the picture is the Keying, the first Chinese junk to sail round the Cape of Good Hope of Africa. Built of teak wood, with a displacement of eight hundred tonnes, the junk was as sturdy and fast as any western vessel at that time. In acquiring this vessel, the British merchants had to overcome many difficulties in Canton because at that time it was strictly forbidden to sell Chinese vessels to foreigners. The Keying survived many storms without major damage. She took only twenty-one days to sail from America to England – which was a very short sail even for an American packet-ship of the time. The Keying is, therefore, the pride of the shipbuilding industries of China.

The highly decorative style of this work shows very well the details of the vessel, particularly her lavish Chinese motifs. The two "eyes" on the bow are characteristic of Chinese junks. They came from the seamen's traditional belief that ships, like man, could "see" the waterway and lead the crew to sail in safety. -

-

Foreign factories in Guangzhou

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1817 – 1819

-

Oil on canvas

-

44 x 59 cm

-

Donated by Sir Paul Chater

In 1757, Emperor Qianlong ordered all trade ports to be closed, with the sole exception of Canton left open to foreign trade. The Qing government commissioned the Cohong, a guild of Chinese merchants (Hong merchants), as sole agents to handle foreign trade affairs. Foreigners were confined to a district outside the city walls to the south of the old city, where the Hong merchants leased riverside premises to them as residences and offices. The district was known as the "Foreign Factories" or the "Thirteen Hongs". "Thirteen" was merely a title; the actual number of foreign countries that rented premises in the district fluctuated. This oil painting shows the flags of the different countries flying in front of the factories they occupied at the time. -

-

Hong Kong from the Mid-Levels looking northwest

-

Marciano Antonio Baptista (1826 – 1896)

-

ca. 1858

-

Watercolour on paper

-

39.4 x 60.4 cm

-

Donated by Sir Paul Chater

In his early years, Marciano Antonio Baptista lived in Macao, where it is believed he served as Chinnery's assistant before finding work as a stage designer. He later moved to Hong Kong, where he concentrated on landscape painting.

This work shows the view from Magazine Gap Road northwest towards Central. On the left is Government House with its gardens, while the Government Secretariat and St. John's Cathedral rise in the middle and Murray Barracks stand on the right. On the other side of the harbour lie Stonecutters Island and Kowloon Peninsula. This view was a favourite of the artist, who created several other paintings with a similar composition. His works are mostly presented in a gradation of close, medium and distant views, with the subjects arranged from near to far and strong colours fading out progressively. The illusion of depth is produced by the aerial perspective. Major buildings are depicted in meticulous detail to highlight their features. -

-

Godowns in Honam, Guangzhou

-

Anonymous

-

ca. 1858

-

Oil on canvas

-

53.5 x 146 cm

-

Donated by Sir Robert HoTung

The godowns on Honam Island on the south side of the Pearl River, opposite the site of the old factories, were built after the destruction of the Hongs in 1856. The godowns remained there until Shamian Island was leased to Western merchants in 1859. Sailing under an American flag, the Willamette belonged to Russell & Company and sailed between Hong Kong and Canton during the months of January to October in 1856 and later from 1858 to 1861.

The paintings of this subject offer several very similar views of the godowns on Honam but with different sidewheelers portrayed in each, while some depict an array of Chinese vessels, giving the impression that perhaps the paintings are meant to be as much about the vessels as about the harbour. This would make sense, as the architecture of Honam was not as distinctive as that of the old factory site. -

Waterfall at Aberdeen, Hong KongBamboo aqueduct, Hong KongVictoria CityBritish naval detachment encamped at KowloonPortrait of Macao sampan girlThe facade of St. Paul's Church, MacaoView of Praya Grande, MacaoMa Kok Temple, MacaoCentral Macao from Penha HillBocca TigrisThe Whampoa anchorageForeign factories in GuangzhouNew China StreetA Cantonese opera sceneA Chinese ladyPortrait of a Western merchant on the China coastSelf-portrait of LamquaProduction of tea: Packing tea for exportA bouquet of flowersThe studio of TingquaBritish officers greeting Chinese mandarinsGuangzhou foreign factories on fire: BeginningExtensive view of Macao from Penha HillA Chinese sampan girlThe Chinese junk, KeyingForeign factories in GuangzhouHong Kong from the Mid-Levels looking northwestGodowns in Honam, Guangzhou