Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Chinese Antiquities

The Chinese Antiquities collection has the widest ranging and oldest art objects and artefacts at the HKMoA. Totaling more than 4,700 items or sets, it includes ceramics produced by various kilns for domestic and export, textiles and other categories such as bronzes, jade carving, lacquer ware, enamel ware, glassware, bamboo carving, wood carving, ivory carving, rhinoceros horn and furniture. Among them, ceramics are the most representative, accounting for over half of the collection and spanning the period from Neolithic to the twentieth century. Fashioned for use in everyday life, as ritual objects, as mingqi (brurial objects) or purely for decoration, each and every piece has fortunately been preserved through the ages, escaping the ravages of time to form an essential part of China's rich cultural heritage. The Chinese Antiquities Collection embody a high degree of creativity and technological skill and thus provide invaluable materials for studying Chinese ancient society and culture.

Given Hong Kong's geographic location, it is natural that tangible art objects of southern China should be a central focus of our collection. As part of our mission to promote the understanding and appreciation of Chinese cultural relics, the Museum has been ardent in its efforts to acquire outstanding artefacts for display, while our collection has been tremendously enriched by generous donations and bequests from the public. Among the most significant of these are a collection of bamboo carvings received from the estate of Dr Ip Yee in 1985, which highlights the close relationship between this art form and the lifestyle of the Chinese scholar, and two collections of Shiwan pottery donated by Woo Kam Chiu in 1986 and by Mrs Kwok On in 1987, which bear testimony to the achievements of the celebrated Guangdong kiln. Equally important, however, are the many other donations our museum have received from numerous different institutions and individuals, and their generosity not only reflects their support of our museum, but is also indicative of the growing awareness of the need to preserve our cultural heritage.

-

Bronze gu with animal mask and kui dragon design

-

Late Shang dynasty (ca. 11th century BCE)

-

Metal (Bronze)

-

H 29.7 cm Dia (mouth) 16.7 cm

Based on archaeological findings, it is now generally agreed that Chinese history entered the early Bronze Age in about 2000 BCE, with the art of bronze casting reaching its peak during the Shang and the Western Zhou dynasties. Most of the bronzes made in these periods were intended for use during rituals and sacrifices, and large numbers of bronzes have been unearthed in Shang tombs.

Wine vessels rank among the most common type of bronzes cast in the Shang period, and this bronze gu is a fine example. With a wide trumpet mouth on a hollow, splayed foot, and a slender waist that is easy to hold with the hand, the upper section from the mouth to the neck is decorated with a vertical blade-shaped plantain design and a band featuring a snake pattern. The main motifs are kui dragons and an animal mask. The animal mask depicting a taotie, a ferocious mythical creature that is a common sight on Shang bronzes. Cast on the waist and splayed base, the mask is symmetrically divided by raised flanges, while the background is filled with the fine incised lines of leiwen thunder patterns. This complex and dense decorative style is typical of the late Shang period, as are the raised flanges, which serve the dual purpose of hiding the casting marks and accentuating the sense of solemnity evoked by the vessel. -

-

Pottery watchtower in green glaze

-

Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

-

Ceramics

-

H 130 cm W 48 cm

It was in the Han dynasty that low-fired lead glazes were first developed. The most common colours used were green and brown, but because of their high lead content and poisonous nature, lead glazes were mainly applied on burial objects known as mingqi.

Belief in the afterlife was strong during the Han dynasty, and it was customary to place a wide variety of mingqi in the tomb, including daily utensils, figurines of attendants and models of architectural structures, to accompany the dead into the next world. This watchtower is typical of the models that were produced throughout central China. Made of red clay covered with a low-fired green glaze, it consists of four sections. Each storey has an overhanging roof with corners ending in upturned leaf-shaped projections, and these roofs are supported by Y-shaped brackets, which are characteristic Han architectural features. A bird with outstretched wings perches on the topmost roof, the balconies are decorated with trellis patterns, while figures look out from the windows to add to the sense of liveliness. -

-

White marble figure of Guanyin

-

Xinghe period (541), Eastern Wei dynasty

-

Stone (Marble)

-

Mark of 3rd year of Xinghe (541) and of the period, Eastern Wei dynasty

-

H 61.5 cm L 18 cm W 23.5 cm

The long dedicatory inscription carved on the four sides of the rectangular base provides important information on this beautiful white marble figure, revealing the date the sculpture was made and the reason why a Buddhist mendicant appeared to the people and advised them to make an image of Guanyin to worship plus a long list of donors.

With a serene facial expression and a calm posture, Guanyin, the Chinese deity of compassion and mercy, stands on a round pedestal with inverted lotus petals supported by the inscribed rectangular base. The mandorla is also shaped as a lotus petal with a pointed tip. The Guanyin wears a petal-shaped crown with a cowl hanging down his shoulders, as well as long flowing robes, the folds of which are represented by low relief lines on the body and end in two rows of stylised ripples at the feet. Flowing ribbons from his shoulders cross in front of the chest, passing through a circular bi-shaped disc. He also wears a simple necklace and holds a lotus in his raised right hand and a receptacle in his lowered left hand. The sculpture still bears some pigment: the mandorla is framed with a green border, and traces of red, green and blue can be found on various parts of the figure. The treatment of the drapery and the shape of the mandorla are both typical of Buddhist sculptures of the Eastern Wei dynasty. -

-

Tomb guardian in sancai glaze

-

Tang dynasty (618 – 907)

-

Ceramics

-

H 70 cm W 20 cm

Developed from the low-fired lead glazes of the Han dynasty, sancai, or three-colour, wares were a new type of ceramics that appeared during the Tang dynasty and were intended for use as burial objects. Two or more metal oxides, such as copper, iron and cobalt, were used as colorants in a lead glaze fired at a low temperature of 800°C, a process that produced different tones of yellow, green, blue, brown, purple and black. The beauty of these glazes lay in their high fluidity, which allowed them to flow down and into each other to create striking gradations of tone and pattern.

The wide range of sancai wares, which have predominantly been found in areas around Xi'an and Luoyang, capital cities during the Tang period, includes utensils, animals, figurines and even architectural models, all of which reflect the customs and beliefs of the Tang nobility.

One such practice that was common among Tang nobles was to protect their tombs with tomb guardians. These fearsome looking creations were usually placed near the entrance or at the four corners of the tomb chamber, from where they could drive away evil spirits. Crouching on an openwork pedestal, this tomb guardian presents a ferocious picture with its impressive horns, staring eyes and full beard, the sharp fangs emerging from its large mouth, the pair of wings stretching out from its shoulders, and its long, hoofed forelegs. The figure is richly covered with yellow, green and creamy white glazes that intermingle on the body. -

-

Pair of square plates with moulded floral design in white glaze

-

Liao dynasty (916 – 1125)

-

Ceramics

-

H 2.5 cm L/W 10.9 cm

Established by the Khitan ethnic group in North China in 916, the rule of the Liao Empire overlapped in large part with the Northern Song dynasty in central China. It was thus natural for the techniques used in its porcelain production–for example, high-fired white wares, low-fired lead-glazed wares and sancai (three-colour) wares–to be greatly influenced by those of the central China. However, distinctive vessel shapes such as the pilgrim flask, the phoenix-head vase, the square dish and the begonia-shape dish reflect a distinctive nomadic style.

With its flat base, flared sides and scalloped edges, this square dish has a unique form that is derived from the wooden prototypes used by the early nomadic Khitans. The body is fine and covered with a lustrous white glaze that resembles Ding ware, while an elaborate moulded design complements its shape. The flared sides are decorated with peonies and leaf scrolls, with four butterflies moulded at each corner, while a coin motif adorns the flat base; a floral design fills the space in-between. Both the butterfly and the coin design were popular decorative motifs during the Song dynasty. -

-

Mallow-shaped flower pot saucer in purple blue glaze, Jun ware

-

Southern Song (1127 – 1279)

-

Ceramics

-

Mark of character 'seven'

-

H 6.5 cm Dia 22 cm

Known as one of the "Five Great Kilns" of China, the Jun kiln was located in Yu county of Henan province (ancient Junzhou) during the Song dynasty. Archaeological discoveries at the Baguadong kiln prove that this particular site was once used to produce imperial wares, especially basins, washers and vases, for Emperor Huizong.

Jun wares are famous for the magnificent way that their thick glazes change to produce such beautiful colours as moon white, sky blue and rose purple. This mallow-shaped flower pot saucer covered with thick, rich purplish-blue Jun glaze has an elegant form with an everted rim. Covered with a brown wash and bearing a ring of small spur marks, the flat base also reveals an incised numeral seven: In fact, one can usually find a numerical inscription on the bottom of Jun ware made in the imperial kiln. There are a number of records documenting the number characters. In The Pure and Rare Collection of Antiquities, one finds that "The best are inscribed with the character one or two". Xu Zhiheng (1877 – 1935) wrote in Porcelain Studies of Yin Liu Zhai that odd numbers were used to mark red vessels and even numbers were for green and blue ones. Theses on Ancient Porcelain by Feng Xianming (1921 – 1993) and other more recent books on archaeology agree that numerals were used to indicate the size of vessels, in descending order from one to ten. Numbering planters also made it easier to pair pot saucers to planters of a corresponding size. This argument is most widely supported by modern scholars but lingering debate suggests that further study is required to reach any sort of a conclusion. -

-

Carved red lacquer box with bird and flower design

-

Yuan dynasty (1271 – 1368)

-

Lacquer

-

Mark of ‘Zhang Cheng Zao' and ‘Yangji'

-

Dia 24.4 cm H 10.9 cm

The resinous sap of the lacquer tree rhus verniciflua has been used by the Chinese as a protective and watertight covering for wood and other vessels since the Neolithic period. It was during the Yuan and early Ming that the most accomplished carved lacquers were produced, and among these the wares produced by Zhang Cheng and Yang Mao of Jiaxing in Zhejiang province are renowned for their fine technique and lustrous finish.

This red lacquer box belongs to the work of Zhang Cheng. The slightly rounded cover is carved with two herons in flight above a bed of hibiscus on a buff background, while the straight sides are decorated with bands of flowers of the four seasons. A layer of black lacquer is inserted in between the red, and two parallel grooves are carved on the outside of the foot ring. The base is lacquered in black. Distinguished by its fine craftsmanship and attractive decorative design, the box features an incised mark of Zhang Cheng on the left side and also red Phags-pa inscriptions reading ‘Yangji' painted on the centre of the base and on the inside of the cover. -

-

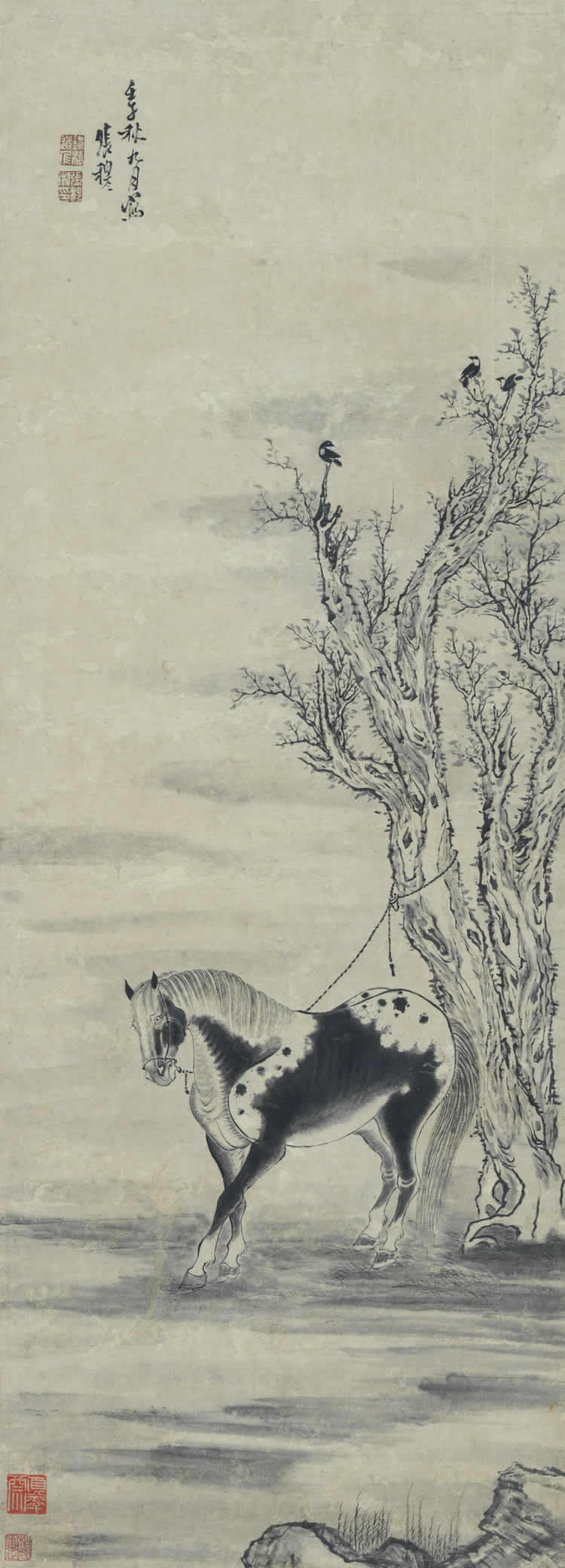

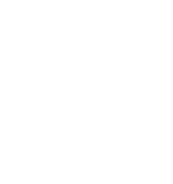

Vase with applied chi-dragon decoration and scrolling peony design in underglaze blue

-

The fifth year of Tianshun period (1461), Ming dynasty

-

Ceramics

-

Dated the fifth year of Tianshun period (1461), Ming dynasty

-

H 32 cm Dia (mouth) 4.4 cm Dia (belly) 21.2 cm Dia (foot ring) 10.4 cm

The twenty-nine years covering the reigns of Zhengtong, Jingtai and Tianshun have long been considered an interregnum in the history of Chinese ceramics. Production at the imperial kiln at Jingdezhen was interrupted as a result of social unrest and economic problems, and although production was still carried out at the various folk kilns, works dating from these three reigns are extremely rare. Most of the pieces that have been discovered and dated to this period are underglaze blue wares.

This heavily potted vase has a long neck, short shoulders, bulging body and a flat, glazed base. The foot ring has been removed. The decoration is divided into three sections by underglaze blue horizontal lines. The first section consists of a chi-dragon applied in relief and coiled around the neck of the vase against a background of auspicious emblems; the lower part is decorated with rocks and grass. The second section consists of continuous peony scrolls around the belly, while the third, on the underside of the belly, contains a 47–character–inscription recording that it was an altarpiece dedicated by a man called Cheng Chang and his wife in Duoyuanwang village, Xiameitiandu, praying for a prosperous officialdom. Bearing the date of the fifth year of Tianshun (1461) of the Ming dynasty, the vase is a prized item of great value for research and study. -

-

Bowl with flower scroll design in underglaze red

-

Hongwu period (1368 – 1398), Ming dynasty

-

Ceramics

-

H 10 cm Dia 20.1 cm

Underglaze red, a decoration painted with copper oxide under a layer of transparent glaze, was first developed in Jingdezhen during the Yuan dynasty, but the technique underwent rapid advances during the reigns of the emperors Xuande (1426 – 1435), Kangxi (1662 – 1722) and Yongzheng (1723 – 1735). The red colour was obtained from firing at a high temperature in reducing atmosphere. A very difficult technique to control, successful examples with bright red effects are very rare.

Produced in the Hongwu period in the early Ming dynasty, this bowl has a slightly flaring mouth, a deep belly and a circular foot ring. The white glaze reveals a greenish tint. Cracks can be found over the entire body of the bowl, and there are rust stains and some small unglazed points where the glaze was not coherently fired. Both the interior and exterior sides of the bowl are painted with underglaze red designs, while the foot and the rim are decorated with key fret patterns. On the inside, the centre of the bowl is painted with a large peony branch within a double line border. The interior wall is decorated with chrysanthemum scrolls and the exterior wall with peony scrolls.

With its smooth flowing lines and distinctive pattern, the bowl is regarded as a highly representative piece of the underglaze red wares produced during the early Ming dynasty. -

-

Stem cup with lotus design in doucai technique

-

Chenghua period (1465 – 1487), Ming dynasty

-

Ceramics

-

Six-character mark of Chenghua and of the period (1465-1487), Ming dynasty

-

H 7.7 cm Dia (mouth) 6.1 cm

The use of doucai enamels began in the Xuande period (1426 – 1435) of the Ming dynasty, but the technique was brought to maturity in the Chenghua period. The term doucai, literally "contesting colours", refers to the coexistence of underglaze and overglaze decorations on the same item. The design would first be outlined or partially painted in cobalt blue pigment, then the entire vessel would be coated with a transparent glaze and fired at a high temperature. Next, coloured enamels would be applied over the surface of the glaze to complete the design, before the vessel was fired a second time at a lower temperature.

This stem cup has gently curved sides, a deep belly and a tall, splayed stem foot. The exterior is decorated with a lotus design, where the petals and leaves are outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with overglaze red, yellow and green. A single line border in underglaze blue marks the interior and exterior of the mouth rim and is repeated on the splayed foot. The base of the splayed stem is hollow. The base bears a six-character mark of the Chenghua period inscribed in underglaze blue in two columns of regular script. With its well-balanced form, its thin, light porcelain body and its finely painted decoration, this stem cup ranks among the finest doucai enamelled wares of the period. -

-

Bamboo toad carved in the round

-

Zhu Ying (act. Ming to early Qing dynasty)

-

16th / 17th century

-

Bamboo

-

H 2.8 cm L 4.9 cm

-

Mark of ‘Zhu Ying'

-

Donated by Dr Ip Yee

The bamboo is a plant much admired by the Chinese for its utilitarian functions as well as its beauty, and its hollow, segmented form has long been eulogised as an emblem of humility and righteousness of the scholar. By the late Ming period, thanks to the patronage of the literati and the emergence of several great artists in this field, bamboo carving had developed into a significant art form. Jiading (in today's Shanghai) and Jinling (today's Nanjing) in Jiangsu province became the two main centres for bamboo carving at that time.

This bamboo toad carved in the round, with the two-character mark of ‘Zhu Ying' in relief on its belly, belongs to the work of Zhu Ying, a renowned bamboo carver who was active in Jiading in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Specialising in high relief work and carvings in the round, the members of the Zhu family (the father Zhu He, his son Ying and grandson Zhizheng) were reputed to be the greatest bamboo carvers of the time, with Zhu Ying particularly known for his carvings of toads, immortals and mountains. This work makes clever use of the natural effect of the gnarled protrusions of the bamboo root for the eyes and the markings of the creature, while the form of the root is ideal for transforming into the toad's natural posture. All of these features demonstrate the artist's complete mastery of his medium. -

-

Jade water container in the form of a mythical animal

-

16th century

-

Jade

-

H 6.7 cm L 15.8 cm W 13.8 cm

Jade occupies an eminent position in ancient Chinese culture: treasured for the intrinsic beauty of the stone, including its colour and texture, and the skill with which it is fashioned, it has been used throughout the centuries for ritual objects, weapons, tools, status symbols and ornaments, as well as for burial purposes.

Carved out of green jade with yellowish brown markings, this water container is probably shaped in the form of a tuolong, a mythical animal with the shell of a tortoise, the head of a dragon – including a single horn, comma-shaped ears, bulging eyes and flaming eyebrows, a scaly neck and body, and feet with five claws. The base presents a whirlpool, with the crests of the waves lapping over the edge to form part of the shell, which is carved with a hexagonal pattern and a border representing thunder (square spirals). Small nodules down the middle of the shell indicate the position of the spine, and in the centre is a small circular hollow for holding water.

The bulging eyes, truncated snout and the hexagonal pattern on the shell are all characteristic features of Ming dynasty animal carvings, with the whirlpool pattern in particular typical of sixteenth century designs. The fine details and large size of this piece are both indicative of the fact that it is a magnificent example of Ming jade carving. -

-

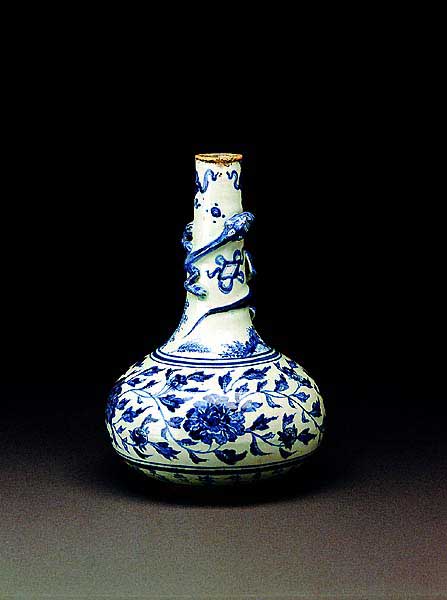

Painted enamel vase in double gourd shape with bird and flower design in reserved panels

-

Qianlong period (1736 – 1795), Qing dynasty

-

Enamel (Painted enamel)

-

H 56.5 cm Dia (belly) 33 cm

The use of enamel was introduced to China in the Ming dynasty and was applied to vessels of metal, ceramics and glass. This last technique was brought to China by sea from Europe in the early Qing dynasty and was first learned and reproduced by the Cantonese. A layer of opaque enamel has first to be applied onto the copper vessel before firing to achieve a smooth surface. Next, coloured enamels are painted over the enamelled surface, before the vessel is fired a second time to complete the production process.

In the shape of a double gourd with a lobed, copper body, this vase is painted in polychrome enamels with a wash technique on a stippled yellow ground. The body is decorated with double gourds, vines (symbolic of the wish for many sons), grass scrolls, white plum blossom, leaves, butterflies and grasshoppers. Two reserved panels on the lobed belly are decorated with blossoming apple branches and birds and butterflies on a sky blue background. The unusually large size, the superb quality of the painting and the bright colours mark this vase out as one of the finest works in painted enamel. -

-

Bowl with the emblems of the Eight Immortals in doucai enamels

-

Qianlong period (1736 – 1795), Qing dynasty

-

Ceramics

-

Six-character mark of Qianlong and of the period (1736 - 1795), Qing dynasty

-

H 5.4 cm Dia 20 cm

-

Donated by the National Museum of Chinese History, Beijing

During the Qianlong reign of the Qing dynasty, polychrome wares reached new heights both in terms of the quantity and technical perfection of their production. This bowl in doucai technique is in the shape of a conical bamboo hat with a flared mouth, a broad rim, shallow sides and a tall foot. The cavetto is painted with the emblems of the Eight Daoist Immortals entwined with flower sprigs, while the exterior is covered with sprays of flowers of the four seasons. The flowers and branches would first have been outlined in underglaze blue and then filled with overglaze enamels to produce the brilliant doucai colour contrast. A six-character mark of Qianlong is written in seal script in underglaze blue on the base.

Legendary figures in Daoism, the Eight Immortals were widely used as decorative motifs during the Qing dynasty. Sometimes, as in this bowl, only the attributes of the Eight Immortals would be depicted. Thus here we see Tieguai Li's gourd, Lu Dongbin's sword, Zhang Guolao's 𝘺𝘶𝘨𝘶 (bamboo drum), Han Zhongli's fan, He Xiangu's lotus, Han Xiangzi's flute, Lan Caihe's flower basket and Cao Guojiu's castanets. As is the case with the Eight Immortals to which they belong, these emblems represent longevity. -

-

Ivory snuff bottle in the shape of a goose

-

Qianlong period (1736 – 1795), Qing dynasty

-

Ivory

-

Four-character mark of Qianlong and of the period (1736-1795), Qing dynasty

-

H 3 cm L 4.7 cm

The taking of snuff–made by grinding tobacco to a fine powder – and the exchange of snuff bottles were very popular social customs in Europe as early as the sixteenth century, but it was not until the late Ming period that they were introduced to China. Initially only practised at court, the habit spread to the general public during the Qing dynasty, when the Chinese began to devise their own snuff bottles, which then became reflections of social status. Snuff bottles were made from a large variety of materials, including metal, porcelain, jade, lacquer, glass, ivory and bamboo, and they thus form a representation in miniature of traditional Chinese decorative art.

This snuff bottle was produced by the Beijing Palace Workshop. In the shape of a goose, the entire body is carved with fine lines to suggest the bird's feathers. The eyes are inlaid in black; the head is embellished with a semi-precious stone in red and the beak inlaid with horn. The cover is fashioned as a hinged section carved out of the goose's breast, while underneath is a stopper with a spatula for scooping the snuff. The webbed feet are folded under the body and realistically depicted with brown staining. The entire piece is ingeniously conceived yet depicted with great naturalism. The inside of the hinged cover bears a four-character mark of the Qianlong period.

The Qianlong emperor was particularly fond of intricate ivory carvings, and this snuff bottle exemplifies the best eighteenth century ivory carvings. With its clever design, perfect sense of proportion, superb carving and fine details, it is considered an outstanding artefact of the period. -

-

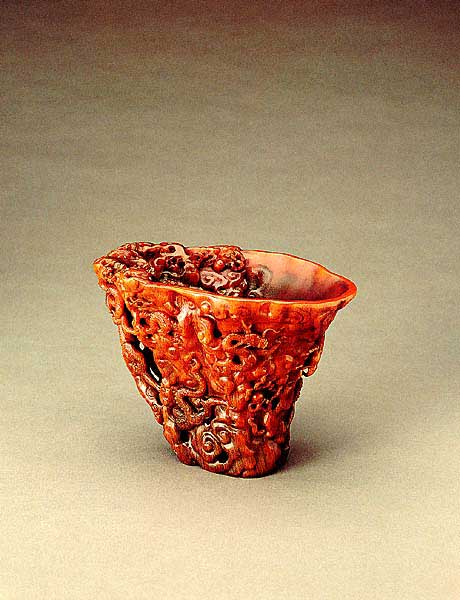

Rhinoceros horn libation cup carved with nine dragons in high relief

-

Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911)

-

Rhinoceros horn

-

H 13.6 cm L 18 cm W 12 cm

Chinese medical lore credits rhinoceros horn with antipyretic, antidotal and aphrodisiac properties. With a natural tapering shape, it is not surprising that most of the vessels made from rhinoceros horn that can be found today are libation cups.

This libation cup with a tapered base is carved out of a large piece of rhinoceros horn in a rich honey-brown tone with dark brown areas at the base and extending to the inside. Finely carved in high relief and openwork, nine dragons chase flaming pearls amid clouds and rocky crags, clambering upwards and over the rim to form a cup handle and through the sides to the interior.

The use of mature scaly dragons on rhinoceros horn carvings as on this cup is very rare (the chi-dragon is the more commonly found species). An even more special feature is the total of nine dragons with four claws carved on the cup, strongly suggesting that it was made for imperial use. -

-

Glass vase with landscape and figure design in transparent red overlay on snowflake white ground

-

Second half of 18th century

-

Glass

-

H 28.6 cm Dia (belly) 13.8 cm

Glass is a synthetic substance made by fusing quartz and lead, barium, sodium and calcium at a high firing temperature. Glassmaking has a long history that dates back about 2,500 years in China.

Possessing a pronounced preference for glass objects, Emperor Kangxi of the Qing dynasty ordered an imperial glass workshop to be established under the management of the Palace Workshop (Zaobanchu), to which workers were recruited primarily from the two main glass production centres at Boshan in Shandong province and Guangzhou in Guangdong province. At the same time, glassware used by the common people was produced in a number of regional glassmaking centres including Yanshenzhen of Boshan, Guangzhou and Suzhou. Glassmaking thus underwent significant development during the Qing dynasty.

This vase has a globular body and a tall cylindrical neck. The snowflake white background is overlaid with a layer of red glass, while the main decoration is a landscape with figures, supplemented by plantain leaves around the neck and lotus petals on the shoulders. The relief carving is finely executed to varying depths, and the careful control of space, the balanced composition and the contrast in colour exemplify the artistic style and technical excellence of glassmaking and decoration in eighteenth century China. -

-

Lady's headdress tianzi with bats, butterflies and flowers in pearls, semi-precious stones and kingfisher feather inlay

-

Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911)

-

Kingfisher feather, pearl and semi-precious stones

-

L 29 cm W 16.5 cm

Throughout the dynasties, the Chinese government imposed strict regulations on official costumes, stipulating the materials, colours and motifs that could be used to indicate the wearer's rank and position. In the Qing dynasty, Manchu ladies were allowed to wear the tianzi (headdress) with changfu (casual wear) and the jifu (festive costume).

Flat-topped and shaped like an inverted winnowing basket, this headdress was worn at an angle. The framework is constructed of very thin rattan or iron wire covered with black silk gauze, with the black frame then decorated with delicate groups of ornaments in the shape of flowers, birds and auspicious motifs (such as bats, an emblem of long life). The outlines are formed by gilt filigree work and set with semi-precious stones and kingfisher feathers, decorations that were very popular during the Qing dynasty. This tianzi is fully bedecked with motifs and further embellished with a border of dangling pearls and stones falling from the back, suggesting that it was intended to be worn on festive occasions to accompany the jifu. -

-

Bodhidharma

-

Liu Chuan (1916 – 2000)

-

Mid 20th century

-

Ceramics

-

H 47 cm

-

Seal of ‘Wanxi Liu Chuan'

The Shiwan kiln in Foshan is one of the most important folk kilns in Guangdong. Shiwan wares can be divided into two categories, namely daily utensils and artistic figurines, and of these it is the Shiwan pottery figurines, modelled in a vigorous manner reflecting the rich folk traditions of the area, that are most well-known. Most of the subjects represented in the figurines are drawn from folklore, legends and popular drama.

This is the figure of Bodhidharma, one of the most important Buddhist characters, who is said to have arrived in China in 520 CE. He was once invited by Emperor Wudi of the Southern Liang dynasty to discuss Buddhism but following a divergence of views Bodhidharma left and went to stay at the Shaolin monastery.

The base of this Bodhidharma is inscribed ‘Wanxi Liu Chuan' in seal script characters, indicating that it was made by Liu Chuan before 1960. Reputed to be the best twentieth century Shiwan potter second only to Pan Yushu, Liu Chuan excelled in modelling figures that express life and individuality. The body of this figure is first made by moulding and the details and the face are made by hand modelling. The lively facial expression and delicate modelling of draperies of the Bodhidharma all reveal the exceptional talent of the potter. Shiwan figures are also renowned for their bright and brilliant glazes; the pomegranate red applied on this figure was just one of the distinctive glazes successfully fired in the Shiwan kiln during the Qing dynasty and the twentieth century. -

-

Pouch-shaped glass vase with chi-dragon and floral scroll design in painted enamels

-

Qianlong period (1736 – 1795), Qing dynasty

-

Glass

-

Four-character mark of Qianlong and of the period (1736-1795), Qing dynasty

-

H 18.5 cm

This glass vase resembles a yellow pouch. A silk band in relief ties around the neck. The white glass body is adorned with eye-catching, painted enamel designs that imitate the texture of silk and cloth. The ground, which also imitates brocade, is painted with fine patterns composed of peonies, hibiscuses, peach blossoms, and pomegranate flowers. On top of these are twelve painted chi-dragons that wind around and through the branches and flowers, forming a well-coordinated and close-knit composition. Lively and graceful in form, the dragons also harmonise with the floral patterns on the ground.

Enamel-painting on glass is a very technically demanding craft, began under the Kangxi Emperor's reign (1662-1722). In 1696, Kangxi decreed that a glass factory be established. This factory expanded continuously during the high Qing and created large quantities of glass products and gifts for the court. Glassware produced during the reigns of Yongzheng (1723-1735) and Qianlong reached a peak, whether in the variety of vessel types, colouring, composition, or ornamentation. This glass vase reflects the intricate and sumptuous ornamental style of the Qianlong reign. The decorative patterns are ornate and dense, demonstrating the excellent craftsmanship. The back features a flower bud bearing the reign mark of the Qianlong period. A product of a thoughtful designer, this vase can be said to be a masterpiece among Qianlong glassware. -

-

Emperor's dragon robe embroidered with the Twelve Imperial Symbols

-

Xianfeng period (1851 – 1861), Qing dynasty

-

Silk (Embroidery)

-

H 144 cm W 204 cm

This bright-yellow dragon robe has a round collar, overlapping lapel and horse-hoof cuffs. The robe is embroidered with three dragons on the chest and at the back – one front-facing, and two in profile. In addition, there are two front-facing dragons on either shoulder, and one on the inner facing which only becomes visible when the lapel is turned down. Therefore it makes a total of nine dragons on one robe, with five always in view from whatever angle. This is an indication of the Emperor's status as the "Son of Heaven". A dragon robe of this design is the emperor's formal attire for rituals and ceremonies.

The Twelve Imperial Symbols are unique to dragon robes worn by the Qing emperors. They symbolize a ruler's power and embodiment of the highest virtues. The twelve symbols are: the Sun, representing the illumination of the myriad things; the Moon, representing yin-yang balance; a constellation of Stars, representing harmony with the heavenly laws; mountains, representing steadfastness; dragon patterns, representing deft adaptation to change; the huachong pheasant standing on one leg, representing impressive literary cultivation; a pair of yi libation cups meant for ancestral worship, representing loyalty and filial piety, wisdom and courage; water weed, representing purity and cleanness; flame, representing brightness; millet, representing material plenitude; a sacrificial axe, representing decisive and acute judgment; and a fu symbol, representing the ability to distinguish clearly between right and wrong. Since the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), there had been multiple interpretations of the twelve symbols, but generally speaking they were thought to signify the worship of Heaven, glorification of ancestors, making-manifest of ritual propriety, and veneration of morality. -

-

Liu Hai with a three-legged toad, Shiwan ware

-

Liu Chuan (1916 – 2000)

-

Early 20th century

-

Ceramics

-

H 29.4 cm

-

Seal of ‘Wanxi Liu Chuan'

-

Donated by Mr Woo Kam Chiu

This ceramic sculpture comes from the famous kilns of Shiwan and depicts the scene of "Liu Hai teasing the three-legged toad". Liu, sitting on a large boulder, is trying to catch a toad in a crevice with a string of gold coins. The figure comes alive with the portrayal, while the boulder, the toad and the folds in Liu's robe are fluidly and vividly articulated in detail. Created by the famous modern Shiwan master, Liu Chuan (1916 - 2000) in his later years, it carries the maker's mark "Wanxi Liu Chuan" on the back.

Liu Hai is a legendary figure popularly found in Chinese folklore. Born "Liu Haichan", he was a hedonist during the first half of his life before he gave up wealth and material satisfaction to pursue the Taoist way of transcendence. Accompanied by a three-legged toad, he would perform magic tricks by scattering coins in the marketplace as lessons to abstain from material wealth. The stories finally evolved into this image of "Liu Hai teasing the three-legged toad".

The image grew so popular that later, both the figure of Liu Hai and his toad have come to be regarded as auspicious deities, scattering money everywhere they went. The image can be found in New Year pictures, in ceramics, and in carvings in jade, bamboo, wood and ivory. -

-

Pottery brazier with cicadas in green glaze

-

Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

-

Ceramics

-

H 10.4 cm L 24 cm W 15.8 cm

This pottery brazier is a burial object from the Han dynasty. It has four sides that slope inwards, with slits in the base. Notice its animal and geometric patterns on the four sides. And look at its feet. Can you see how the bears are supporting the heavy weight of the brazier? On top, which is the grill, there are two rows of cicadas, four on each side. This reflects the Han custom of eating cicadas.

During the Han dynasty, the popularity of burying pottery figures, animals and utensils with the dead led to massive demand, and massive production. In ancient China, it was believed that the cicada could give the deceased the power of reincarnation. The pottery burial objects that have survived to this day, such as houses, barns, servants, people, utensils and various other objects for everyday living, show us how the Han people lived 2,000 years ago and what they believed about life after death.

Most of the burial objects of the Han period used glazes fluxed with lead for low temperature firing. For the brazier here, a bright green glaze was originally used, but prolonged exposure to water has turned the high lead content into the silvery colour we see here. In fact, because of this high lead content, glazed wares were only used as burial objects. -

-

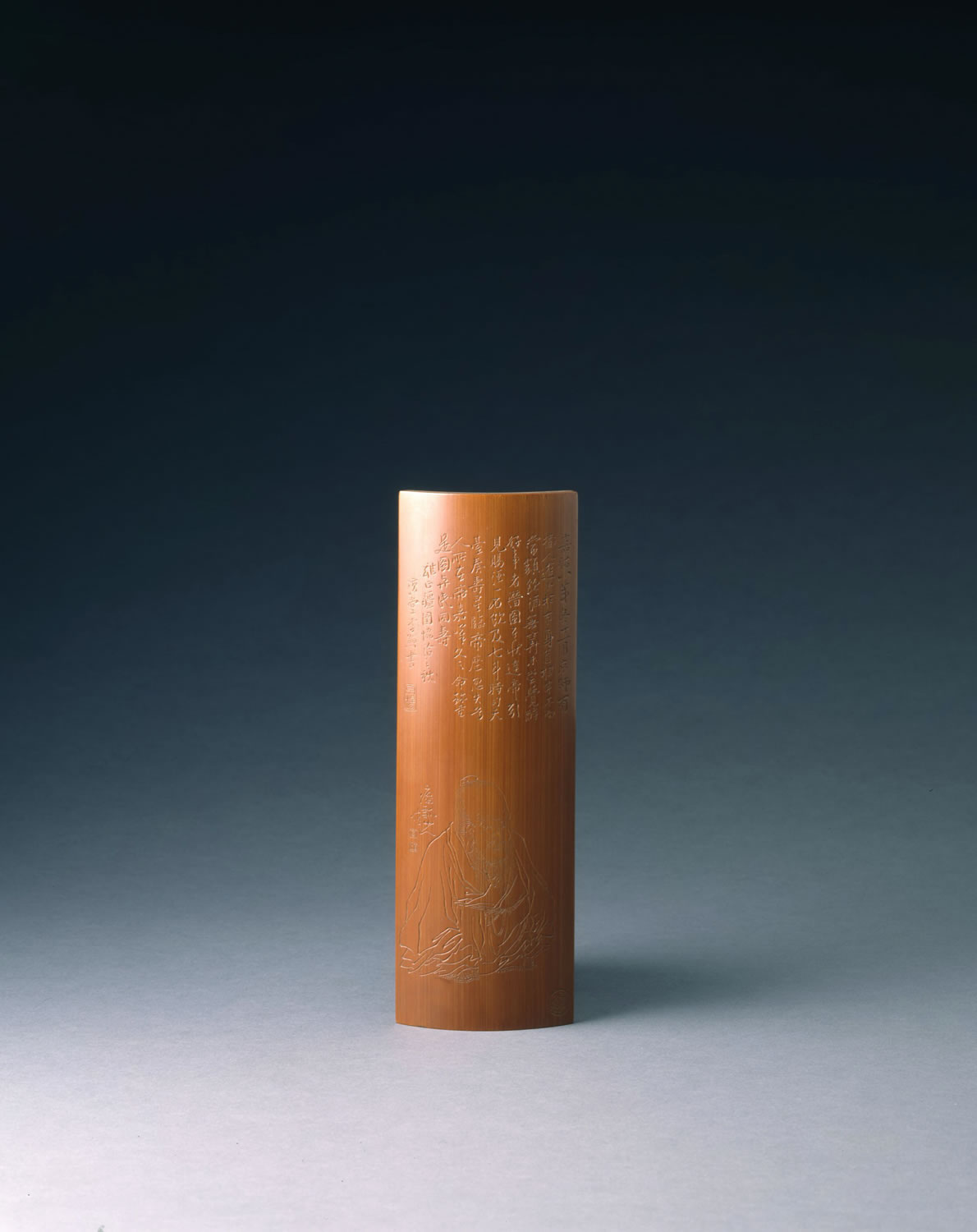

Wrist-rest lightly engraved with an image of the God of Longevity

-

Qianlong period (1736 – 1795), Qing dynasty

-

Bamboo

-

H 22.5 cm W 4.4 cm

-

Donated by Dr Ip Yee

This wrist-rest is a collaborative work by Li Shan, Huang Shen and Pan Xifeng, three masters of the Qing dynasty. Active in Yangzhou in Jiangsu province during the Qianlong period, Li Shan and Huang Shen were two of the "Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou", who advocated innovative styles of painting, while Pan Xifeng's exquisite craftsmanship in bamboo carving made him one of the most eminent bamboo carvers of the Jinling School.

On the lower part of the wrist-rest is a lightly engraved image of the God of Longevity made by Pan Xifeng, who completed the work by engraving his seal "Xifeng" in the lower right hand corner of the wrist-rest. The features of the God of Longevity–for example his beard and eyebrows–have been finely and meticulously executed to capture the shape and spirit of the character and to bring the figure to life. The folds of the clothes and the inscription on the upper part of the wrist-rest, written by Li Shan, embody the charm, the radiance and the power of Huang Shen's painting and Li Shan's calligraphy. -

-

Bowl with four paper-cut phoenix patterns in black glaze, Jizhou ware

-

Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279)

-

Ceramics

-

H 6.5 cm W 16 cm

-

Donated by Mr and Mrs Kwok Sau Po

The outer surface of this bowl is finished in a tortoiseshell glaze while the inside is adorned with a yellow-brown transmutation glaze on a black background. Four reserve phoenix patterns circle the mouth and a plum blossom can be seen in the centre.

This type of paper-cut pattern bowl is typical of Jiangxi Jizhou ware. Jizhou potters excelled in creating transmutation glazes and paper-cut decorations using two different glazes, and in fact this design method became a unique feature of Jizhou ware. It consists in creating an exterior tortoiseshell glaze by intentionally applying a lighter colour on the ferric base glaze. During firing, the two glaze colours fuse and melt into a tortoiseshell pattern. Decorative cutout patterns were created using a similar method. Potters would apply paper-cut patterns to the base glaze of the vessel. After this glaze was topped with a glaze of a lighter colour, neat and clean-cut patterns would result in addition to the transmutation glaze effect. This technique is known as paper-cut and is a unique feature of the workmanship developed by Jizhou potters. -

Bronze gu with animal mask and kui dragon designPottery watchtower in green glazeWhite marble figure of GuanyinTomb guardian in sancai glazePair of square plates with moulded floral design in white glazeMallow-shaped flower pot saucer in purple blue glaze, Jun wareCarved red lacquer box with bird and flower designVase with applied chi-dragon decoration and scrolling peony design in underglaze blueBowl with flower scroll design in underglaze redStem cup with lotus design in doucai techniqueBamboo toad carved in the roundJade water container in the form of a mythical animalPainted enamel vase in double gourd shape with bird and flower design in reserved panelsBowl with the emblems of the Eight Immortals in doucai enamelsIvory snuff bottle in the shape of a gooseRhinoceros horn libation cup carved with nine dragons in high reliefGlass vase with landscape and figure design in transparent red overlay on snowflake white groundLady's headdress tianzi with bats, butterflies and flowers in pearls, semi-precious stones and kingfisher feather inlayBodhidharmaPouch-shaped glass vase with chi-dragon and floral scroll design in painted enamelsEmperor's dragon robe embroidered with the Twelve Imperial SymbolsLiu Hai with a three-legged toad, Shiwan warePottery brazier with cicadas in green glazeWrist-rest lightly engraved with an image of the God of LongevityBowl with four paper-cut phoenix patterns in black glaze, Jizhou ware